Your guide to Chicano Park in the Barrio Logan neighborhood of San Diego, including how it came to be, featured artists, information on the museum and more.

By Maura Fox | San Diego Union-Tribune | APR. 19, 2023 | Photo by Howard Lipin

Chicano Park, located in Barrio Logan, is one of San Diego’s most culturally significant landmarks with a story rooted in collective activism and the power of art.

Located beneath Interstate 5 and the on-ramps for the San Diego-Coronado Bridge, the park was established in 1970 as a result of protests not long after construction of the bridge was completed. Today, it stakes the claim of holding the largest collection of outdoor murals in the world, with more than 100 of them painted on the freeway pillars, depicting messages and images of strength, struggle and community in Indigenous, Mexican and Mexican American history.

“I consider the park to be a sacred space, and I say that because of the rich history behind it, with regards to the many steps and many stories and many activities that have happened here,”said Alberto Pulido, a University of San Diego professor and member of the Chicano Park Steering Committee, which serves as the steward of the park.

Just as the park is connected to the past, it’s also closely linked to the current community, its ongoing activism and its future. There is a newly opened Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center next to the park, and new murals are being painted, with many younger artists rising up to contribute.

Here’s a look at the history and significance of the park, along with its artists, murals and hopes for the future.

History

In the early 1900s, Barrio Logan was part of a larger area known as Logan Heights. Its Mexican and Mexican American population grew as a result of immigration after the Mexican Revolution, as well as a development boom along the waterfront, which led to an increase in job and housing opportunities in the area, according to a historical survey done for the city in 2011.

However, by the 1930s, the Great Depression led to economic instability and Mexican workers faced racism, hostility and deportation. A report examining redlining practices in the 1930s in San Diego found that the area containing what’s now known as Barrio Logan, Logan Heights and Grant Hill was given a “D” letter grade by the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, meaning it recommended its lenders refuse to give loans in the area, saying it was “occupied by mixed races, colored, Mexican, lower salaried white race, laborers.”

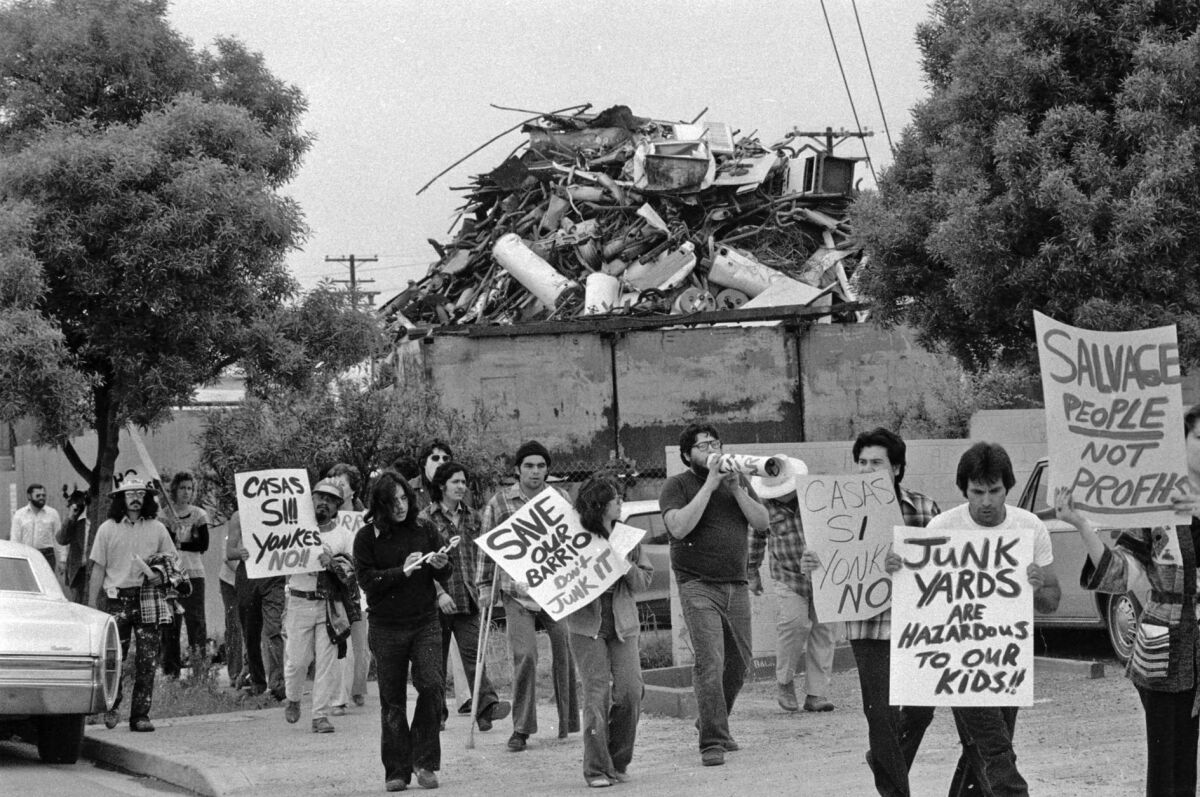

During and after World War II, the Mexican American community in Logan Heights grew, in some cases because of the Bracero Program bringing in more workers from Mexico. In the 1950s, the neighborhood was rezoned and transformed from a mostly residential area to mixed-use, where metal shops, junkyards and factories were built around homes. Highly industrialized, the neighborhood became “the city’s auto junkyard capital.” Heading into the 1960s, a social and economic protest movement was growing among Mexican Americans, many of whom preferred to use the term Chicanos.

In 1963, the California Department of Transportation built Interstate 5 through Logan Heights, followed by the San Diego-Coronado Bridge construction four years later, effectively cutting the neighborhood in half. The northernmost part was called Logan Heights, with the southern part referred to as Barrio Logan. Thousands of residents, whose homes were in the construction’s path, were forced to move.

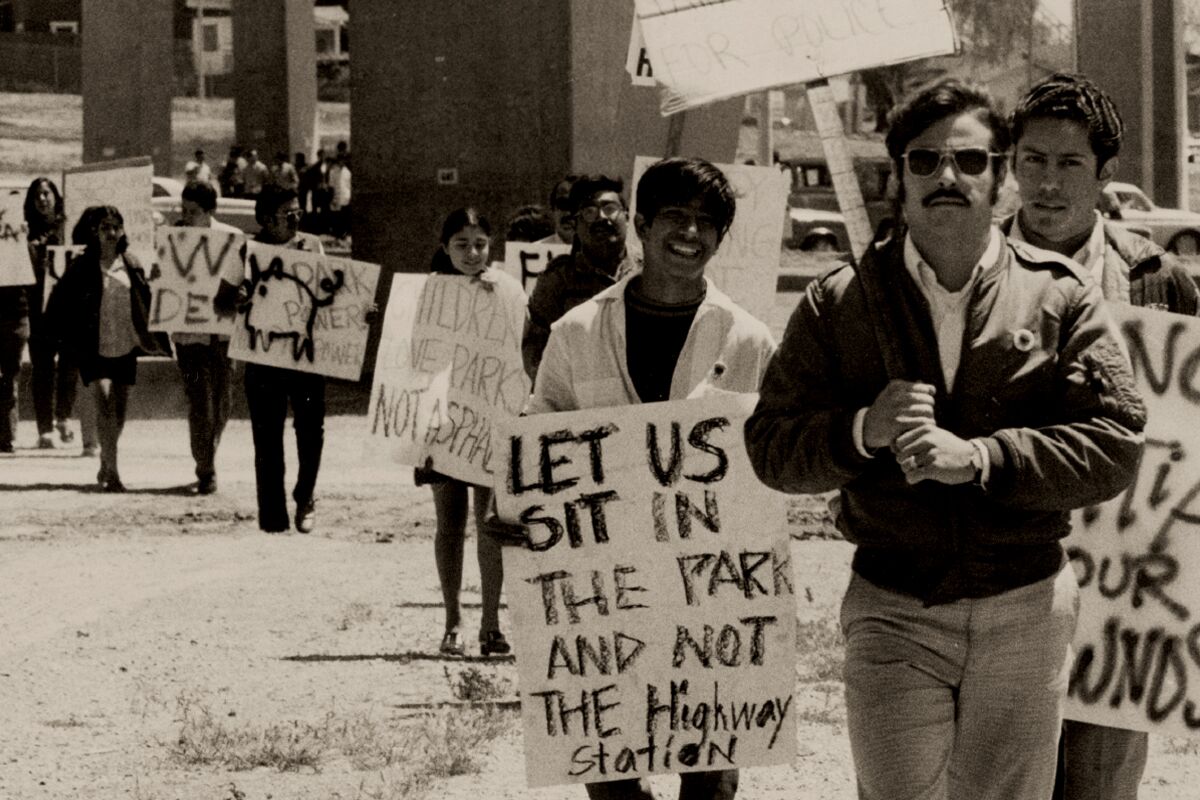

The attempted construction of a highway patrol station in the area in 1970 sparked an organizing effort by Barrio Logan residents and Chicano activists, who protested the development, occupying the park for 12 days until an agreement was reached between the community, state officials and the city of San Diego to support the creation of a community park.

Salvador Robert Torres, often referred to as the “architect of the dream,” was the visionary for the park’s design and murals, saying at the time that “Chicano artists and sculptors would turn the great columns of the bridge approach into things of beauty, reflecting Mexican American culture.”

By 1973, mural projects had begun. In 2013, Chicano Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2017 it was established as a National Historic Landmark. Today, the park is technically owned by the California Department of Transportation, though the artists own the murals.

Chicano Park named National Historic Landmark

Jan. 11, 2017

“The revolutionary part of the park is that the vehicle of destruction, which was the bridge and the pillars, was redefined by the community and through the creative spirit of art,” Pulido said. “And now it’s ours.”

Prominent murals and artists

Over the past 53 years, more than 100 murals and sculptures have been created under the freeway overpasses, with new ones in the works. The pieces depict key moments in Indigenous history, revolutionary struggles and achievements, Chicano identity and important figures like Che Guevara, Frida Kahlo and Emiliano Zapata. Find a map of the murals here.

The first mural painted in the park, in 1973, is “Historical Mural,” located on Logan Avenue on the side of the I-5 freeway on-ramp. Created by Toltecas en Aztlán, a collective of Chicano artists that also founded the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park, the mural presents a sweeping history of Chicano culture and the contributions of Spanish, Mexican and Mexican American people.

One of the most well-known murals is “Hasta La Bahia,” translated to “All the way to the bay,” which can be found toward the center of the park overlooking National Avenue. Painted by Victor Ochoa in 1978, the phrase refers to a campaign throughout the 1970s and ‘80s to extend the park to the San Diego Bay.

Ochoa is a pioneer in Chicano Park’s history and community, has painted or contributed to dozens of murals in the park and served on the Chicano Park Steering Committee.

“I paint murals from the attitude of the ‘60s and ‘70s, which is kind of issue-oriented,” Ochoa told The San Diego Union-Tribune in 2021. “I want people to be proud of who they are. The history of the community is really important to me.”

Along with “Hasta La Bahia,” Ochoa’s other murals in the park include “Revolución Mexicana,” completed in 1985, and “Brown Image,” a tribute to Mexican American lowrider culture and the newest mural, completed in 2022. The mural was painted using airbrushing techniques with gold metal flakes, traditionally used to paint lowrider cars.

San Diego, California - January 25: Roberto R. Pozos, 60, helps paint a five-story mural called “Brown Image” on a pillar in Chicano Park that features images from car clubs from the 70s on Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022 in San Diego, California. Eight artists are airbrushing the piece and using techniques that would typically be used to paint a lowrider car. The pillar is being painted a candy apple root beer color mixed with 30 pounds of metal flake which is about 18 cars worth of material. A fundraiser for the volunteer artists will be held on Feb. 5. (Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Mario Torero’s “Colossus,” painted in 1975, is another mural that shouldn’t be missed, depicting an Atlas-like figure who seems to be holding up the freeway on-ramp. Like Ochoa, Torero is one of the park’s original muralists and activists.

Women artists were also critical to the park’s mural development. Yolanda Lopez was an accomplished muralist and advocate for young female artists, including a group called Mujeres Muralistas, who completed the mural “Preserve Our Heritage” in 1977.

Charlotte “Carlotta” Hernandez, an artist and singer, designed the Chicano Park logo, which today resides on a pillar with the phrase “La Tierra Mia,” or “my land.”

New museum and educational opportunities

The Chicano Park Museum and Cultural Center opened in the fall of 2022, creating a space to educate visitors about Chicano, Latino and Indigenous culture and history. The museum, located directly next to the park, has a main exhibit called “PILLARS: Stories of Resilience and Self-Determination,” which highlights the groups that contributed to Chicano Park and the region.

There is also a rotating gallery to showcase local artists’ work.

The museum has partnered with the Logan Heights Archival Documentation Project, an effort led by Pulido, who has been instrumental in documenting the area’s history with help from students.

The project’s detailed research on key places and moments in Logan Heights history, including the timeless restaurant El Carrito and the original Logan Heights library, can be found on the museum website here.

The museum is open Friday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Visiting Chicano Park

Plan to spend at least an hour walking around the 7.4-acre park and admiring the murals, or bring a lunch to sit on the grass or at one of the many tables positioned throughout.

Before going to the park, it’s helpful to know general information about the murals and their significance, so try to stop by the museum first. Other information can be found in this 2015 Chicano Park Murals Documentation Project. The Chicano Park Steering Committee also leads walking tours through the park for visitors to learn even more.

While a large portion of the park and its murals reside between Logan and National avenues, visitors will also find additional murals in the basketball courts on Logan Avenue, along with a community herb garden. Make time to walk around the surrounding neighborhoods, as well, where there are shops, restaurants, art galleries and more murals painted on gates and the sides of buildings.

The future of the park

Artists are still painting new murals today. Mario Chacon, an artist and community advocate, is currently working on a mural on the southwestern side of the park — but Pulido notes that as less space becomes available, there’s more competition for artists to claim a pillar or location to paint. From 2016 to 2022, 17 murals were added to the park. Several murals, painted decades ago, have also been restored.

Cindy Rocha, Hector Villegas , Patricia Cruz and Cesar Castañeda are among the newer muralists in the park. To paint there, a muralist must first bring a design to the Chicano Park Steering Committee for approval and ensure funding to complete the work.

Cruz, who is also a member of the steering committee, said that the younger generation is aware they are standing on the shoulders of the artists who painted before them in a more “revolutionary” era.

However, the new generation still has issues to contend with in Barrio Logan, Pulido said, citing gentrification concerns and poor air quality. Barrio Logan suffers some of the worst air quality in California, according to regulators, and concerns over how the city responds to pollution in the neighborhood remains a top issue for the community.

“It’s more than murals and pillars,” Pulido said. “What will Chicano Park look like 20 years from now? Will we still have this energy?”