By: Michelle Alexander ~ The New York Times ~ May 13, 2020

I have been wondering what to say about the horror of Covid-19 behind bars. Much has already been written about the scale of the crisis, the moral argument for freeing people from prisons and jails, and the utter inadequacy of the response in many states, including New York.

Activists, community leaders, medical experts and family members of people who are incarcerated have been raising their voices to little avail. In recent weeks, I sensed something was missing from the public debate but struggled to name it.

Then I read a letter from a man in Marion Correctional Institution in Ohio. Suddenly the answer was obvious.

In Ohio, my home state, more than 80 percent of the people caged at Marion have been infected with the coronavirus because of the state’s lackluster response. Thirteen have died. Last month, the Ohio Prisoners Justice League and Ohio Organizing Collaborative demanded that Gov. Mike DeWine release 20,000 prisoners, about 40 percent of those in state custody, by the end of May. That number would encompass those whose sentences are nearly complete, those imprisoned for “nonviolent” offenses, elderlypeople and those with health problems that render them especially vulnerable to infection.

In response to coronavirus concerns, Governor DeWine commuted seven sentences and created an opaque process through which the prison population may have been trimmed by roughly 1,300. The bulk of the reduction has been accomplished through diversions to alternative programs that lowered new prison admissions rather than through releases. About 200 people have been recommended for early release.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people crammed in the state’s prisons fear for their lives. This crisis could have been averted if the governor had been willing to free people en masse when the risk to the caged population became clear.

- Help us report in critical moments.

While the coalition’s demand to release 20,000 people might strike some as unreasonable, Gary Daniels, the chief lobbyist at the A.C.L.U. of Ohio insists that figure should actually be viewed as a floor considering the scale of the crisis.

“The system is already 10,000 above capacity,” he told me. “Roughly 22 percent of people are there for technical violations of their post-release conditions. And the No. 1 reason people end up in prison is for drug offenses. Releasing 20,000 is the baseline.”

Mr. Daniels is right. Our nation’s prison population has quintupledover the last few decades; we lock up and lock out more peoplethan any other country on earth — overwhelmingly poor people and people of color. Viewed in this light, cutting the prison population by less than half in order to prevent unnecessary suffering and death is hardly an unreasonable demand.

As I see it, people who have been convicted of violent crimes — not just nonviolent ones — should be considered for possible release. Why should we exclude from consideration someone convicted of armed robbery at 18, who’s still locked up at age 45, simply because he has two more years left on his sentence? Our governments have been willing to shut down our entire economy, sparing only those sectors deemed “essential.” Shouldn’t we also consider whether it is truly “essential” for millions of people to be caged?

Saying that it has been difficult to persuade policymakers to listen to the voices of those most affected would be a gross understatement. Given the restrictions on public gatherings, activists have had to become remarkably creative.

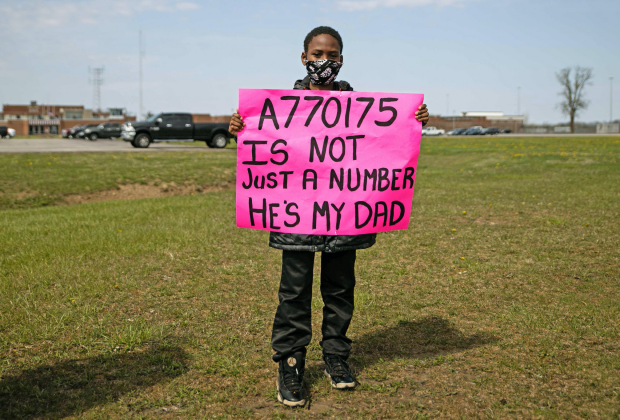

In April, people from all over Ohio held a protest in Columbus to draw attention to the coronavirus crisis behind bars. More than 100 cars, filled with friends, loved ones and allies of those locked in cages circled the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction and waved signs reading “Prisoners’ Lives Matter.”

The car caravan then proceeded to the Statehouse, where about 50 people staged a “socially distant die-out.” People lay in rows, six feet apart, as though they were about to be buried. Supporters chanted the slogan “20K by May,” and one family in attendance had children carrying signs pleading for their father’s life.

In the days after the protest, I wondered what could be said that might make a difference. Facts, data, medical evidence and pleas from family members have not been enough to stir a meaningful response. I asked myself and others: What has not yet been said? What do people need to hear?

And then I read the letter.

It was shared with me, with the writer’s permission, by one of my colleagues. To protect this man from possible retaliation from administrators and guards, I cannot tell you his name or the name of the addressee. I cannot tell you whether he was convicted of a minor crime or a serious one. Those details do not matter in any event.

What you need to know is that he, like many other people imprisoned today, is demonstrating a higher level of moral clarity and compassion in this crisis than many of us, especially elected officials who would rather let people die in cages than let them go months or years ahead of schedule.

I recognize that prison officials may dispute some of claims in this letter. Last month, a spokesperson for the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction said “There is no shortage of cleaning supplies, and inmates have access to soap and other hygiene products, hand sanitizer and masks.” However, the conditions described here have been echoed by others, and the author makes a larger point that deserves to be heard. This is what he wrote, abbreviated and lightly edited for clarity:

I walked to the back of the dorm today to check on my friend. He is confined to his bed by Covid-19. Weakness, fatigue, intense vertigo and difficulty breathing allow him to leave his bed area only to defecate (he has to urinate in a drinking jug) or an occasional shower.

It has been two weeks now. I have somehow become his nurse. I cook and help with laundry, homework and whatever else he needs.

He was asleep. I was relieved. I finally had a moment of rest. These last two corona-months have been crazy. I have been sick, helping the sick, or both.

Along my way to the day room, I met a nurse who’d just finished passing out daily medications. I asked her if we’d be retested for the virus. After testing positive with over 2,000 other men, and with the symptoms seeming to linger and even reoccur, I am eager to be retested. It has been over 14 days since the tests. We should be negative by now. I am concerned that we are reinfecting each other.

The middle-aged nurse, with the sweetest demeanor, gave me her undivided attention and began to speak comfortingly to me. This is a rarity in prison; nurses are usually curt and distracted. So I tuned in.

She assured me that we would be retested at some point. I should be patient. The nursing staff really cares about us, she said, even those who act a “little snobby.” I shouldn’t listen to what was being said in the hallways; they’re taking good care of us. Everyone who needs serious medical attention is being sent out.

The proof of their commitment to us is the fact that they are here. They could have quit like other nurses. I should look at the bright side. Even with all the cases, only a few have had to be sent to outside hospitals.

As she spoke, I thought of my friend I was trying to nurse back to health. She knew nothing of this man because, while his case is documented, no one has come to examine him. A cursory glance will show anyone how serious his condition is. Neither he nor I have notified the staff because we know from other friends’ experiences that he will be thrown into a cell and left to his own devices. We believe that we — unqualified inmates — can do better.

I also thought of another friend who, only now after two weeks, is beginning to walk on his own again. The virus hit him hard. At one point he had such difficulty breathing that we thought for certain he would die. We frantically scrambled around trying all sorts of remedies, while insisting that the guards alert the medical staff. The nurses refused to come.

For hours, we fought for his life. The only thing that helped was boiling water and Vicks 44 in a crock pot and allowing him to inhale the steam. In the meantime, we contacted his family and told them to contact the administration incessantly. After about 3 ½ hours, the nurse arrived. She took him to the medical area.

Less than an hour later, we watched him be carried back into the building by two officers. He still wasn’t walking on his own. His friends — his fellow prisoners — have taken it upon themselves to nurse him back to health ever since.

As I pictured these things, she continued to explain why we should be grateful that we are receiving any care at all. She encouraged me to tell the men around me to be grateful in spite of the two-month delay in the issuing of commissary items. I wondered how grateful she would be without toothpaste and soap, or how her mood would change if the state shortened food rations and wouldn’t allow her to buy a few snacks.

She said the officers were doing their best and that they didn’t have to be here. They were working only because they care. She said they were volunteering to do things. She recounted how sad it was that one officer almost “threw in the towel” because of all of the ungratefulness.

I struggled to understand what she meant by “volunteer.” The officers are not only paid but paid extra for their efforts. I suspect that if the pay were to stop, they would stop. She waxed passionate when she talked about how some officers had to handle garbage (a job normally reserved for inmates). That sight affected her deeply. She was impressed by people who would willingly handle garbage for a short period of time for $22 an hour but considered it normal for prisoners to do it every day for $22 a month.

The conversation saddened me because the nurse meant well. She was sincere. She was one of the good ones. She reminded me of one of the “moderates” Dr. King talked about in his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.” If the good people feel this way, then we are really in trouble. Despite all her passion, her main agenda was not to hear my needs or concerns or to help address them; it was to provoke passivity, assuage anger, and prevent revolt. She was alright if my problems didn’t go away as long as I didn’t make too much of a fuss about it. She is convinced that prisoners should be grateful for deficient medical care and two-month lapses between access to vital necessities, hygiene products and sanitation services. Those are things that we don’t deserve and shouldn’t expect or feel entitled to. I’m certain she doesn’t feel this way about everyone. She wouldn’t see her daughter locked in a room with Covid-19 and no medical care and say, “Well, you know, you lucked out, honey.”

She just feels this way about prisoners. The social category of prisoner qualifies one as undeserving of a decent civilized life.Herein lies the cause of the profound spread of the virus throughout the institution: the collective sense of the undeservingness of prisoners. A vaccination would be nice. Proper P.P.E. would help. But the real cure for our woes is an affirmation of the inalienable entitlement to life for people in prisons and jails.

After reading this letter, I took a deep breath. I had to admit to myself that there was a time when I was that nurse. I was a well-intentioned, sincere person who viewed myself as working for social justice yet unconsciously believed that the lives of some people matter a bit less.

Perhaps you are that nurse today. If you’re completely honest with yourself, do you believe that “we,” the so-called innocent, are more valuable than “them,” the “criminals”? Do you believe the lives of those locked up or locked out matter a bit less and they should be grateful for any care or concern at all?

We now face a choice regarding what kind of country we want to be in the months and years to come. Rather than imagining that the lives of those locked in cages are less valuable than our own, perhaps we ought to get down on our knees and say, “There but for the grace of God go I.” I do not even consider myself a Christian and yet those are the only words that spring to mind when I think of all those at Marion Correctional, including our letter writer, as well as all those in prisons and jails nationwide, whose lives have been discarded in the era of mass incarceration.

It may be tempting to believe, if you’ve never been locked up, that you could never find yourself in prison. Yet most of us, at some point in our lives, have committed crimes that could result in prison time, such as illegal drug possession or theft. Some of us, due to poverty, trauma, oppression or mental health challenges, have gone through periods in which we made grave mistakes or caused serious harm to others.

Equally important is the fact that who’s behind bars today has more to do with our collective choices than individual ones. Our nation has spent trillions on endless war and systems of mass incarceration and mass deportation; yet basic human rights such as a living wage, health care, housing and quality education are routinely denied on the grounds that we — the richest country in the world — cannot afford to provide to all of our people what citizens of many other nations are granted as a matter of right. If we had invested heavily in the communities that need it most, rather than pouring our resources into policing, surveillance, prisons and jails, most of the people who are behind bars today would not need to be freed by a group of protesters staging a “die-out” on the Statehouse grounds.

It is precisely because of our collective choices that so many of us have friends and family who are incarcerated during this crisis. One in 4 women have a loved one behind bars; the figure is nearly 1 in 2 for black women. As the coronavirus sweeps through prisons and jails, millions of people are living in terror that their loved ones will not escape their cages alive.

More than 95 percent of people in prison will come home one day, if they live that long. The issue is not whether they should come home but when. According to a recent study by the A.C.L.U., failure to aggressively decarcerate could add 100,000 fatalities to the overall U.S. death count ─ among people both in and outside of jail.

Fortunately, California has released nearly 10,000 people from prisons and jails and hopefully will release many more. But most states are responding like Ohio, even though national pollingindicates that 66 percent of likely voters support measures to reduce prison overcrowding in response to the coronavirus, including a clear majority who support various forms of decarceration.

If we, as communities and as a nation, fail to free people in this pandemic because we’d rather risk their lives than allow them to come home earlier than our criminal injustice system originally planned, we should consider ourselves guilty of utter disregard for human life.

Let our people go.

Source: Michelle Alexander ~ The New York Times ~ May 13, 2020