By Rich Archbold | Press Telegarm | Mar. 24, 2024 | Photo By Howard Freshman

These six civil rights activists may have added a few more gray hairs since they led the

way for Latino rights in Long Beach five decades ago — but they haven’t lost their

fighting spirit.

They raised their clenched fists last week in an enthusiastic sign of solidarity for their

years of hard work helping thousands of their fellow community members who were

struggling with economic, educational and many other disadvantages.

“We’re still warriors,” said Ron Arias, a member of the Long Beach Chicano Community

History Committee, which has been dubbed the “Chicano Six.”

Committee members nodded in agreement.

The Chicano Six — which includes Arias and his wife, Phyllis Arias, as well as Carmen

Perez, Armando Vazques-Ramos, Margie Rodriguez and Theresa Marino – have partnered with the Long Beach Historical Society to tell the story of Centro de la Raza, a neighborhood center that started in 1969 and had a major impact on improving the lives of Latinos in the city.

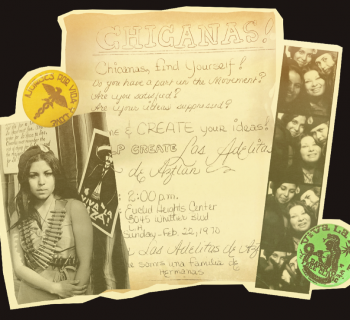

That story will be told through photographs taken by John Taboada, a teacher who

documented the work of Centro and its impact on Long Beach through the years. This

will be the first time his historic photos will be put on public display. The exhibition will

open to the public at the Historical Society, 4260 Atlantic Ave., from 1 to 5 p.m. Friday,

March 29, and will run throughout the year.

“I am thrilled that the Long Beach Chicano Community History Committee trusted the

Historical Society with its history,” said Julie Bartolotto, executive director of the

Historical Society. “The exhibition will add significant knowledge to the public’s

consciousness of Long Beach in the 1970s and early 1980s.”

The Chicano Six worked closely with the Historical Society’s staff, including project

manager Brian Chavez and program and design manager Bianca Moreno.

During the 1960s, Long Beach experienced the largest and fastest growth of the city’s

Mexican American/Chicano population, which exploded 400% from 1960 to 1970,

according to Vazquez-Ramos, one of the first directors at Centro. Spanish-speaking

residents in Long Beach grew from 7,500 in 1960 to 28,500 in 1970. Today, the Latino

population has grown to be the city’s largest ethnic group and will soon become more

than half of the city’s residents, Vazquez-Ramos said.

“It was against the political upheaval, cultural turmoil, civil uprisings and the national

trauma of assassinations of civil rights leaders of the 1960s that the East Long Beach

Neighborhood Center was established,” Vazquez-Ramos said, referring to the early

name for Centro.

It was one of five local neighborhood centers funded by the federal War on Poverty. By

this time, activists had taken on the name “Chicano,” which had long been a racial slur

and now was being worn with pride.

In March 1968, as many as 22,000 mostly Mexican American students walked out of

their classrooms at seven East Los Angeles schools, garnering national attention about

inequities.

That helped galvanize the Chicano civil rights movement.

Many of the same inequalities existed in Long Beach.

It was these conditions that spawned the Chicano Six, most of whom were In their late

teens or early 20s when they became involved in their activism work.

The only member of the Chicano Six who was a little older was Perez.

Perez was born in East LA, the ninth of 10 children. From humble beginnings, she rose to

become an influential and fearless leader in Long Beach.

Her resume includes working as a teacher while raising four children, serving as a patient support services director for Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, being appointed as the first Latina to the Long Beach harbor commission, becoming vice chair of the National Democratic

Party and becoming the founding member of the Long Beach Chicano Political Caucus.

Now, she is a proud grandma and great-grandma — but is still as feisty and fearless as

ever.

Her philosophy for years has been: “Nothing is easy. If you want change, you make it

happen. No one will do it for you.”

Marino, her good friend, affectionately calls her “jefe” (boss) and “godmother.”

At a planning meeting of the Chicano Six at the Historical Society last week, Perez said

activists years ago came to one decision.

“We decided that we had to sit at the same table with other decision makers in the city,”

Perez said. “We did not want to be left out anymore.

“I take pride in what we’ve done,” she added. “We are now at those decision tables.”

Vazquez-Ramos, meanwhile, was born and raised in Mexico City and came to the United

States “like everyone else, for economic opportunity.”

He went to high school in East Los Angeles but came to Long Beach to attend Cal State

Long Beach and became an activist against the Vietnam War and a supporter of Cesar

Chavez in his fight for farmworkers.

Vazquez-Ramos remembers an incident while he was a student on the Long Beach

campus, when an older man saw him carrying some stickers for a grape boycott and said,

“Young man, you can’t have those stickers on this campus.”

Vazquez-Ramos said he found out later that the man was a professor who became head

of the school’s liberal arts department.

“During this time, I was acquiring this Chicano identity,” Vazquez-Ramos said. “If I can do

this, I can help others.”

He said he is more active now as president and CEO/founder of the California-Mexican

Studies Center in Long Beach.

“I am ecstatic with what I have achieved,” he said. “Unfortunately, this exhibit comes with

the passing of JT (John Taboada). We’ve made progress, but there still is so much to do.”

He called on young people to take a greater role in helping people.

“It’s your time to step up,” he said, addressing younger people.

Rodriguez was born in Pomona in 1949 but was raised in Chino and spent much of her

childhood working in peach and walnut fields in Sacramento and Bakersfield.

“I missed a lot of school because of that, but I loved school,” she said.

She started working at Centro and eventually taught kindergarten to fourth-grade in

Lynwood and became a principal in the Montebello School District.

“What made me a warrior and a fighter was seeing the inequities in education and police

brutality,” she said. “That put fire in my belly and why I became a teacher and principal.”

Despite a visual impairment, Rodriguez still volunteers where she can. She also said she

sees progress with civil rights.

“But I agree with Armando,” she added. “Much more work needs to be done.”

Marino is the only non-Chicano of the Chicano Six. She was born in Whittier to parents

who were first-generation children of immigrants from Sicily.

“But I’m an adopted Chicano,” she said.

Marino has had a diverse career, including being a public health official for Long Beach

and working on countless nonprofits. She also played an important role with the Long

Beach City College Senior Studies program.

She was one of nine siblings. She remembers the day she went to a friend’s house to play

— and was jolted by the reception.

“My friend’s mother answered the door and said, ‘Get out of here, you dirty Mexican,’”

she said.

Because of that and other instances, Marino said, she saw what Mexican Americans

were going through, motivating her to help them.

“I was influenced by Carmen and Phyllis,” she said. “We all felt the energy of Centro. It

was powerful and doing so much good. I learned compassion and love at Centro.”

Ron and Phyllis Arias were childhood sweethearts, meeting at Palm Springs High School

and marrying in 1971.

They both have spent a lifetime helping others.

Ron Arias came to Long Beach as a college student and became actively involved in

campus and Centro activities. He later became the director of the Long Beach health

department.

“What motivated me to get involved was the fact that we as people were, like, non-

existent,” he said. “We connected with Cesar Chavez and what he was saying.

“I love Long Beach and the diversity of the city,” Ron Arias added. “I am also a hardcore

American. My father was a Marine on Iwo Jima during World War II. He instilled in us

that we were Americans, but I saw problems that needed to be fixed.”

Phyllis Arias retired as a teacher from Long Beach City College. During her teaching

career, she won many awards. She was a member of the city’s Civil Service Commission

and has been appointed by Mayor Rex Richardson to the city’s Airport Advisory

Commission.

“I got involved with the others because I saw how people were struggling,” she said. “We

just weren’t on anyone’s radar.

Phyllis Arias said she worries now that the younger generation is not aware of Chicano

history and what so many people struggled through.

Thanks to the work of John Taboada, that legacy will live on.

Taboada was born in Indio in 1947. He was raised in an environment of ranching and

agriculture. Coachella Valley was a grape growing capital of California, and his father

was a ranch and vineyard manager for Bob Hope, according to Ron Arias, who has

written a short biography of his friend, who also attended Palm Springs High School,

excelling in cross-country and track and field.

Taboada, known as JT by his friends, attended College of the Desert but transferred to

CSULB and majored in art. He joined the Chicano movement while at CSULB and began

working at Centro de la Raza as an art teacher and photographer.

“John was known for saving everything,” Ron Arias said. “His negatives lived in

cardboard boxes tucked away for many years. In his final months of life, John spent

countless hours digitizing them. In doing so, he saved the legacy of the Centro and the

history of the Chicano Movement in Long Beach.”

Taboada died of tongue cancer last year.

“One of JT’s wishes before he passed was that his photos could be seen by young

people,” Phyllis Arias said. “I am hoping that will happen with this great exhibit.”