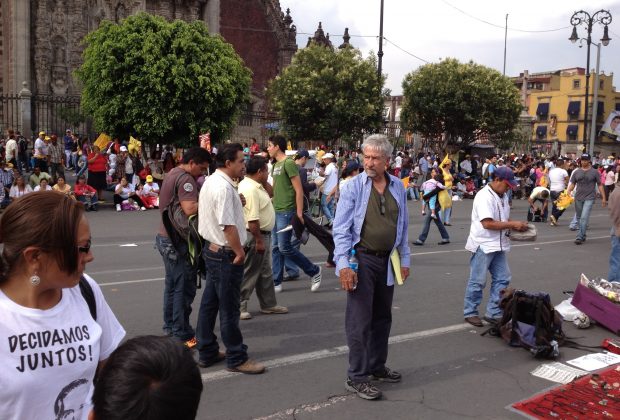

Memorable photographs of Tom Hayden taken Professor Armando Vazquez-Ramos, during a protest march and a visit to the Ho Chi Min memorial on June 27th, 2012 in Mexico City, before the CMSC 2012 Seminar on California-Mexico Policy Issues.

We mourn the loss of Tom Hayden who was an incredible activist and political leader throughout his life, particularly known for his leadership against the Vietnam War.

We were honored to have Tom Hayden in attendance at our 2012 Seminar on California-Mexico Policy Issues, hosted by the the California-Mexico Studies Center and Seminario Permanente de Estudios Chicanos y de Fronteras (DEAS-INAH) at The University of California’s Casa California on June 28 - 30, 2012 in Mexico City, Mexico. As a keynote speaker at the conference, he shared with us his experience and knowledge in a presentation titled, "Student Movements Since The 1960's to #YoSoy132."

We express our gratitude and condolences as we reflect on Tom Hayden's life and legacy.

See the articles from the LA Times and the NY Times below to learn more about this incredible leader.

'The radical inside the system': Tom Hayden, protester-turned-politician, dies at 76

By Michael Finnegan, Los Angeles Times ~ October 23, 2016

http://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-tom-hayden-snap-story.html

Tom Hayden, a 1960s radical who was in the vanguard of the movement to stop the Vietnam War and became one of the nation’s best-known champions of liberal causes, has died in Santa Monica after a lengthy illness. He was 76.

Hayden vaulted into national politics in 1962 as lead author of a student manifesto that became the ideological foundation for demonstrations against the war.

President Nixon’s Justice Department prosecuted Hayden in the raucous “Chicago 7” trial following the violent clashes with police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Hayden later married actress Jane Fonda, and the celebrity couple traveled the nation denouncing the war before forming a California political organization that backed scores of liberal candidates and ballot measures in the 1970s and ’80s, most notably Proposition 65, the anti-toxics measure that requires signs in gas stations, bars and grocery stores that warn of cancer-causing chemicals.

Hayden lost campaigns for U.S. Senate, governor of California and mayor of Los Angeles. But he was elected to the California Assembly in 1982. He served a total of 18 years in the Assembly and state Senate.

During his tenure in the Legislature, representing the liberal Westside, Hayden relished being a thorn in the side of the powerful, including fellow Democrats he saw as too pliant to donors.

“He was the radical inside the system,” said Duane Peterson, a top Hayden advisor in Sacramento.

A longtime target of government surveillance, Hayden took pride in his history of dissent. A photo from the late 1970s shows him pondering, with apparent satisfaction, his 22,000-page FBI file, stacked about 5 feet high.

After the deadly 1967 riots in Newark, N.J., where Hayden had spent several years organizing poor black residents to take on slumlords, city inspectors and others, local FBI agents urged supervisors in Washington to intensify monitoring of Hayden.

“In view of the fact that Hayden is an effective speaker who appeals to intellectual groups and has also worked with and supported the Negro people in their program in Newark, it is recommended that he be placed on the Rabble Rouser Index,” they wrote.

Hayden’s charisma, drive and intellectual heft made him a potent force. “Tom had the gift of articulating the larger meaning of smaller events,” said Todd Gitlin, a writer who succeeded Hayden as president of Students for a Democratic Society, a flagship organizer of 1960s protests. “He was very crisp and clear and unlikely to be at a loss for words as a public voice.”

Hayden, who enjoyed media attention and was skilled at attracting it, worked closely with militant radicals but was equally at ease with the likes of governors and presidents. “He’s always been someone who would much prefer to work and get things done than stand on the sidelines and protest,” Fonda once said.

Born Dec. 11, 1939, Hayden grew up in middle-class Royal Oak, Mich., a Detroit suburb. His father, John Hayden, was an accountant at Chrysler; his mother, Genevieve Garity, was a film librarian at local schools.

At the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Hayden was editor in chief of the campus newspaper and was captivated by the burgeoning civil rights movement in the South.In 1960, he hitchhiked to California to cover the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, where John F. Kennedy was nominated for president.

Soon after, Hayden made his first journey south for civil rights work, driving to rural Tennessee with fellow students in a station wagon packed with clothing and food for black sharecroppers who’d been evicted from their homes after registering to vote. Hayden returned to the South in 1961. He and a friend were beaten and arrested at a civil rights march in McComb, Miss., in a rural area where few blacks dared to vote.

On his 22nd birthday, Hayden was arrested again in Albany, Ga. He’d been in a “Freedom Ride” group of black and white students who, on a train from Atlanta, ignored an order to leave the “white” car, then got thrown in jail for blocking the sidewalk upon arrival in Albany.

“To those who did not pass through the Southern civil rights experience, willfully going to jail may seem like a career-threatening act of despair,” Hayden wrote in his 1988 memoir, “Reunion.” “It was not. It was both a necessary moral act and a rite of passage into serious commitment.”

In 1962, Hayden joined dozens of other students at a Students for a Democratic Society convention in Port Huron, Mich. As primary author of the group’s Port Huron Statement, he gave voice to a youth disaffection that foreshadowed the explosive power of the antiwar and civil rights protests of the years ahead.

“We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit,” the manifesto began.

Inspired by sociologist C. Wright Mills and French author Albert Camus, among others, Hayden and his fellow students bemoaned poverty, racial bigotry, the Democratic Party’s tolerance of Southern segregationists, the threat of nuclear war and an apathetic citizenry. They called for mobilizing students and like-minded Americans through “participatory democracy.”

“If we appear to seek the unattainable, as it has been said, then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable,” the statement concluded.

Before long, the Vietnam War, the draft and violence in the civil rights struggle darkened the nation’s mood and opened sharp racial and generational divides. In Newark, Hayden collected eyewitness complaints as police and National Guard troops waged street battles for six days in the impoverished neighborhoods where he lived and worked. Twenty-six people were killed.

More and more, Hayden focused on opposition to the war — “this slaughter of a distant people,” he called it.

“From the very beginning, Tom played a visionary role in developing strategy for the antiwar movement,” said Bill Zimmerman, a Santa Monica media consultant who was close to Hayden.

Gradually, Hayden’s activism became focused primarily against the war. In 1965 he traveled with an antiwar group to Hanoi, the capital of communist North Vietnam. The 10-day trip offended many in the U.S., and the State Department temporarily withdrew Hayden’s passport.

He returned to Hanoi in 1967 with another antiwar delegation during a period of heavy U.S. bombing. Hayden, wearing a helmet, was forced at one point into a ditch and worried a U.S. bomb would kill him.

The trip ended with a detour to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where an emissary of the Viet Cong, the communist force fighting the U.S., had offered to release three American prisoners of war to Hayden. Initially uneasy, he agreed to the plan. He met the POWs on an airport tarmac, and they boarded a Czechoslovakian plane bound for Beirut. Hayden accompanied the servicemen to the U.S. Embassy.

Nearly two decades later, one of the POWs, Jimmy Jackson, would travel to Sacramento to support Hayden when Republicans were trying to oust him from the Legislature for what they alleged was his treason during the war.

The climax of Hayden’s antiwar work came in 1968, when he and fellow radical Rennie Davis served as co-directors of protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

The nation was torn by social upheaval as the August convention approached. The assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in April had sparked urban riots. Two months later, a gunman killed New York Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles on the night he won California’s Democratic presidential primary.

As protests were spreading across college campuses nationwide, Hayden joined the student occupation of buildings at Columbia University in Manhattan. Police stormed the campus with tear gas. FBI brass in Washington berated local agents in a May 1968 cable for failing to track Hayden at the Columbia revolt. “The investigation of Hayden, as one of the key leaders of the new left movement, is of prime importance to the Bureau,” they wrote.

In Chicago, Hayden and Davis tried for months to get protest permits from Mayor Richard J. Daley’s administration, to no avail. “I told a New York audience that they should come to Chicago prepared to shed their blood,” Hayden recalled in his memoir.

At the convention, thousands of Chicago police and National Guard troops overwhelmed crowds in the street, blasting them with tear gas. Police in blue helmets clubbed front-line protesters, Hayden among them.

“The whole world is watching,” demonstrators chanted as police charged forward. The violence, televised live, contributed to Democrat Hubert Humphrey’s loss to Nixon in November. A government report later called it “a police riot.”

In March 1969, the Justice Department had Hayden and seven others indicted for conspiracy to incite a riot at the convention. The group included Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale and counterculture icons Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, leaders of the Youth International Party, best known as the Yippies.

Frequent courtroom outbursts marred the trial and the judge, Julius J. Hoffman, was openly scornful of the accused and their lawyers. The dramatic high point came when marshals carried out his threat to have Seale gagged and chained to a chair. Seale’s case ended in a mistrial, leaving the “Chicago 7” as the remaining defendants.

Hayden was convicted of traveling across state lines to incite a riot and sentenced to five years in prison. The conviction was overturned on appeal, largely because the judge had sided openly with prosecutors. The government declined to retry Hayden.

After the trial, he moved to a commune in Berkeley but fellow residents kicked him out. They decided “I was an oppressive male chauvinist,” Hayden wrote in his memoir. Angry and humiliated, “I drove away in my beat-up Volkswagen convertible to Los Angeles, the notorious New Left leader and national security threat alone in a world of hurt.”

Hayden’s first marriage, to fellow student activist Sandra Cason, ended in divorce. He crossed paths with Fonda in 1971, when both were speaking at an antiwar event in Michigan. The following year, Hayden saw Fonda again at an antiwar event in Los Angeles. He had just written a book on Vietnam and was traveling the country doing a multimedia “teach-in” on Indochina.

Fonda invited him to her Laurel Canyon house to share his slide show. “I wanted a man in my life I could love, but it had to be someone who could inspire me, teach me, lead me, not be afraid of me. Who better than Tom Hayden?” she wrote in her 2005 autobiography, “My Life So Far.” The couple married in 1973.

By then, Fonda’s 1972 trip to Hanoi had made her a political lightning rod. She’d been photographed sitting in a North Vietnamese antiaircraft gun battery, an incident her detractors considered traitorous and for which she later apologized.

Hayden and Fonda joined forces on an antiwar project, the Indochina Peace Campaign, which lobbied against military funding. Often hounded by protesters, they also went on a national speaking tour with singer Holly Near and former POW George Smith.

Looking back on the war in his memoir, Hayden voiced a few regrets. Time proved him “overly romantic about the Vietnamese revolution,” he wrote. Hayden also admitted “a numbed sensitivity to any anguish or confusion I was causing to U.S. soldiers or to their families — the very people I was trying to save from death and deception.”

As the war came to an end, Hayden embraced mainstream politics in California with a campaign to unseat U.S. Sen. John Tunney. He lost the June 1976 Democratic primary to Tunney, who was ousted in November by Republican S.I. Hayakawa. Some Democrats blamed the defeat on Hayden.

But the campaign laid ground for Hayden and Fonda to start the Campaign for Economic Democracy, later known as Campaign California. The group fought for such causes as Santa Monica rent control, public spending on solar power and divestment from apartheid South Africa.

Much of the group’s money came from Fonda, whose movie career was booming and whose workout video business would spawn a fortune in the ’80s. It helped elect scores of liberals to local offices statewide and campaigned for Proposition 65, the anti-toxics measure that requires signs in gas stations, bars and grocery stores that warn of cancer-causing chemicals.

Hayden represented Santa Monica, Malibu and part of the Westside in Sacramento. His legislative achievements were modest — research into the effects of the herbicide Agent Orange on U.S. servicemen in Vietnam; repair money for the Santa Monica and Malibu piers; tighter rules to prevent the collapse of construction cranes, to name a few.

Hayden paid a personal price for his work as a radical.

His father, a Republican, refused to speak with him for 13 years. They reconciled before his father’s death, a few days before Hayden won election to the Assembly in 1982.

Tom Hayden, Civil Rights and Antiwar Activist Turned Lawmaker, Dies at 76

by Robert D. McFadeen, The New York Times ~ October 24th, 2016

Tom Hayden, who burst out of the 1960s counterculture as a radical leader of America’s civil rights and antiwar movements, but rocked the boat more gently later in life with a progressive political agenda as an author and California state legislator, died on Sunday in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 76.

His wife, Barbara Williams, said he died in a hospital. He had been treated for heart problems and fell ill in July while attending the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. He lived in Los Angeles.

During the racial unrest and antiwar protests of the 1960s and early ’70s, Mr. Hayden was one of the nation’s most visible radicals. He was a founder of Students for a Democratic Society, a defendant in the Chicago Seven trial after riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and a peace activist who married Jane Fonda, went to Hanoi and escorted American prisoners of war home from Vietnam.

As a civil rights worker, he was beaten in Mississippi and jailed in Georgia. In his cell he began writing what became the Port Huron Statement, the political manifesto of S.D.S. and the New Left that envisioned an alliance of college students in a peaceful crusade to overcome what it called repressive government, corporate greed and racism. Its aim was to create a multiracial, egalitarian society.

Like his allies the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who were assassinated in 1968, Mr. Hayden opposed violent protests but backed militant demonstrations, like the occupation of Columbia University campus buildings by students and the burning of draft cards. He also helped plan protests that, as it happened, turned into clashes with the Chicago police outside the Democratic convention.

In 1974, with the Vietnam War in its final stages after American military involvement had all but ended, Mr. Hayden and Ms. Fonda, who were married by then, traveled across Vietnam, talking to people about their lives after years of war, and produced a documentary film, “Introduction to the Enemy.” Detractors labeled it Communist propaganda, but Nora Sayre, reviewing it for The New York Times, called it a “pensive and moving film.”

Later, with the war over and the idealisms of the ’60s fading, Mr. Hayden settled into a new life as a family man, writer and mainstream politician. In 1976, he ran for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate from California, declaring, “The radicalism of the 1960s is fast becoming the common sense of the 1970s.” He lost to the incumbent, Senator John V. Tunney.

But focusing on state and local issues like solar energy and rent control, he won a seat in the California Legislature in Sacramento in 1982. He was an assemblyman for a decade and a state senator from 1993 to 2000, sponsoring bills on the environment, education, public safety and civil rights. He lost a Democratic primary for California governor in 1994, a race for mayor of Los Angeles in 1997 and a bid for a seat on the Los Angeles City Council in 2001.

He was often the target of protests by leftists who called him an outlaw hypocrite, and by Vietnamese refugees and American military veterans who called him a traitor. Conservative news media kept alive the memories of his radical days. In a memoir, “Reunion” (1988), he described himself as a “born-again Middle American” and expressed regret for “romanticizing the Vietnamese” and allowing his antiwar zeal to turn into anti-Americanism.

“His soul-searching and explanations make fascinating reading,” The Boston Globe said, “but do not, he concedes, pacify critics on the left who accuse him of selling out to personal ambition or on the right ‘who tell me to go back to Russia.’ He says he doesn’t care.”

“I get re-elected,” Mr. Hayden told The Globe. “To me, that’s the bottom line. The issues persons like myself are working on are modern, workplace, neighborhood issues.”

Thomas Emmet Hayden was born in Royal Oak, Mich., on Dec. 11, 1939, the only child of John Hayden, an accountant, and the former Genevieve Garity, both Irish Catholics. His parents divorced, and Tom was raised by his mother, a film librarian.

He attended a parish school. The pastor was the Rev. Charles Coughlin, the anti-Semitic radio priest of the 1930s and a right-wing foe of the New Deal.

At Dondero High School in Royal Oak, Mr. Hayden was editor of the student newspaper. His final editorial before graduation in 1957 almost cost him his diploma. In his exhortation to old-fashioned patriotism, he encrypted, in the first letter of each paragraph, an acrostic for “Go to hell.”

His turn to radical politics began at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where he was inspired by student protests against the anti-Communist witch hunts of the House Un-American Activities Committee and by lunch counter sit-ins by black students in Greensboro, N.C. He met Dr. King in California in the summer of 1960 and soon joined sit-in protests and voter registration drives in the South.

Perceiving a need for a national student organization to coordinate civil rights projects around the country, he and 35 like-minded activists formed Students for a Democratic Society at Ann Arbor in 1960. He also became editor of the campus newspaper, The Michigan Daily. He earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology at Michigan in 1961 and did graduate work there in 1962 and 1963.

His marriage in 1961 to Sandra Cason, a civil rights worker, ended after two years. He met Ms. Fonda at an antiwar rally, and they were married in 1973. They had a son, Troy Garity. Ms. Fonda had a daughter, Vanessa, by a previous marriage, to the film director Roger Vadim. Mr. Hayden and Ms. Fonda divorced in 1990.

Mr. Hayden married Ms. Williams, a Canadian actress, in 1993. They adopted a son, Liam. Along with his wife, Mr. Hayden is survived by the three children as well as two grandchildren and a sister, Mary Frey.

Mr. Hayden joined the Freedom Riders on interstate buses in the South in 1961, challenging the authorities who had refused to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings banning segregation on public buses. His jailhouse draft of what became the 25,000-word S.D.S. manifesto was debated, revised and formally adopted at the organization’s first convention, in Port Huron, Mich., in 1962.

“We are people of this generation,” it began, “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

It did not recommend specific programs but attacked the arms race, racial discrimination, bureaucracy and apathy in the face of poverty, and it called for “participatory democracy” and a society based on “fraternity,” “honesty” and “brotherhood.”

Mr. Hayden was elected president of S.D.S. for 1962-63.

He made the first of several trips to Vietnam in 1965, accompanying Herbert Aptheker, a Communist Party theoretician, and Staughton Lynd, a radical professor at Yale. While the visit was technically illegal, it was apparently ignored by the State Department to allow the American peace movement and Hanoi to establish informal contacts. The group went to Hanoi and toured villages and factories in North Vietnam. Mr. Hayden wrote a book, “The Other Side” (1966), about the experience.

At Hanoi’s invitation, he attended a 1967 conference in Bratislava, in what was then Czechoslovakia, and met North Vietnamese leaders, who agreed to release some captured American prisoners as a gesture of “solidarity” with the American peace movement. Mr. Hayden then made a second journey to Hanoi to discuss the details. Soon afterward he picked up three American P.O.W.s at a rendezvous in Cambodia and escorted them home.

Directing an S.D.S. antipoverty project in Newark from 1964 to 1967, Mr. Hayden, in his last year there, witnessed days of rioting, looting and destruction that left 26 people dead and hundreds injured. The experience led to “Rebellion in Newark” (1967), in which he wrote, “Americans have to turn their attention from the lawbreaking violence of the rioters to the original and greater violence of racism.”

In 1968, Mr. Hayden helped plan antiwar protests in Chicago to coincide with the Democratic National Convention. Club-swinging police officers clashed with thousands of demonstrators, injuring hundreds in a televised spectacle that a national commission later called a police riot.

But federal officials charged Mr. Hayden and others with inciting to riot and conspiracy. The Chicago Seven trial became a classic confrontation between radicals and Judge Julius Hoffman, marked by insults, angry judicial outbursts and contempt citations.

In 1970, all seven defendants were acquitted of conspiracy, but Mr. Hayden and four others — Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger and Rennie Davis — were convicted of inciting to riot and sentenced to five years in prison. The verdicts were overturned on appeal, as were various contempt citations, on the basis of judicial bias. Mr. Hayden’s book “Trial” (1970) recounted the events.

(The Chicago Seven trial was originally the Chicago Eight trial, with the Black Panther leader Bobby Seale included as a defendant. After his repeated outbursts in court, calling Judge Hoffman “a pig” and “a fascist,” the judge ordered him bound and gagged in his chair — the image of a black man chained in court shocked many Americans — and later severed his case for a separate trial that was never adjudicated. Judge Hoffman sentenced Mr. Seale to four years in prison on 16 counts of contempt of court, but he served only 21 months before the citations were overturned on appeal.)

Although Ms. Fonda was a wealthy movie star and financially supported Mr. Hayden’s early political career, she and Mr. Hayden lived for years in a modest home in Santa Monica, near the ocean but not on it. They did their own shopping and laundry, cooked meals in a tiny kitchen with an old stove and shared child-care duties for Troy and Vanessa.

Mr. Hayden was Gov. Jerry Brown’s appointed chairman of the SolarCal Council, which encourages solar energy development, from 1978 to 1982. He lost a Democratic primary for governor in 1994 to Kathleen Brown, the governor’s sister, who lost the general election to the Republican governor, Pete Wilson. In 1997, as the Democratic candidate for mayor of Los Angeles, Mr. Hayden lost to the Republican incumbent, Richard J. Riordan.

After his legislative career, he directed the Peace and Justice Resource Center in Culver City, Calif., a platform for his opposition to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He taught at California colleges and at Harvard, and wrote articles for The Times, The Washington Post and The Nation.

Mr. Hayden wrote more than 20 books, including several memoirs, re-examinations of the civil rights and antiwar movements, and volumes on street gangs, Vietnam, his own Irish heritage, the environment and the future of the United States. In 2015, he explored American relations with Cuba in “Listen, Yankee!: Why Cuba Matters.” His last book, “Hell No: The Forgotten Power of the Vietnam Movement,” is to be published early next year by Yale University Press.

His personal papers, 120 boxes covering his life since the 1960s, were given in 2014 to the University of Michigan. Besides troves on civil rights and antiwar activities, they included 22,000 pages of F.B.I. files amassed in a 16-year surveillance of Mr. Hayden.

“One of your prime objectives,” J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime F.B.I. director, said in one memo, “should be to neutralize him in the New Left movement.”