By:

From 1967 to 1977, La Raza, the Los Angeles newspaper turned magazine, provided a vital and dynamic forum for Chicano political and cultural expression. Employing a range of disciplines, including photojournalism, graphic art, satire, poetry and political commentary, it was both chronicler and participant in the Mexican-American struggle for equality and justice.

Marking the 50th anniversary of its founding, the publication is the subject of “La Raza,” a new exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West that documents the relatively unknown story of photography’s important role in the Chicano movement. Opening on Sept. 16, the exhibit was organized by Luis C. Garza, a La Raza photographer and independent curator, and Amy Scott, the museum’s chief curator, and draws from the archive of more than 25,000 images donated by La Raza’s photographers to U.C.L.A.’s Chicano Studies Research Center.

The publication’s title, La Raza, was originally used by the Mexican philosopher and presidential candidate José Vasconcelos in a 1925 essay, “La Raza Cósmica” (“The Cosmic Race”). In it, he argued that the uniquely interconnected identities of the Mexican people, which included European, indigenous, and African roots, presaged a “fifth” race of the future, an agglomeration of all races. While its literal translation is “the race,” the term is typically used to connote the more expansive idea of “the people.”

First published in September 1967, La Raza — which started as a bilingual newspaper and later became a national magazine — began as an organizing tool for the Chicano movement. Mr. Garza noted that its team of activist writers and photojournalists helped give “newfound voice to political, cultural, and artistic expressions.”

“The success and achievement of goals, however ambitious or limited, were tied to organizing and solidifying gains while bringing attention to the grievances and demands of a systematically excluded populace,” wrote Mr. Garza in the exhibition’s catalog. “The intent was to make raza politically and culturally visible, in a way that had never been done before, as self-determining participants in local, national, and global affairs.”

The exhibition is part of a broader initiative led by the Getty Foundation, Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, in which collaborating arts institutions across Southern California explore aspects of Latin American and Latino art from the ancient world to the present. Karen Mary Davalos, a professor of Chicano and Latino studies at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, sees the “La Raza” exhibition as an important opportunity for correcting the tendency of art historians and curators to dismiss or ignore this work.

“We have an art historical language for folk art or objects associated with religious or spiritual experience,” Ms. Davalos said. “Many art historians have dismissed photographs like this as propaganda. And while they see photojournalism as interesting visual imagery, it belongs to a category outside of art. Scholars in Chicano art history have shown how Chicano and Chicana photographers have been blurring this line for decades. They are working with imagery that is certainly aesthetic, but also documentary.”

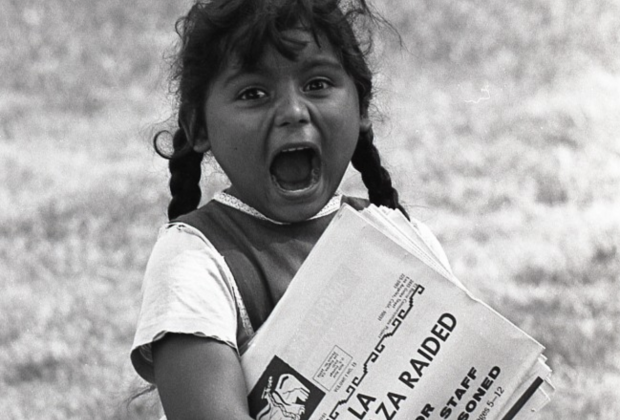

Some of the most compelling images in La Raza depict protest: Oscar Castillo’s portrait of a proud mother and daughter marching down Whittier Boulevard in East Los Angeles during the National Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War in August 1970; Mr. Garza’s photograph of Chicanas with peace sign and Mexican flag at a rally protesting police brutality; Manuel G. Barrera Jr.’s shot of a troubadour at a United Farm Workers rally; and Patricia Borjon-Lopez’s photo of a march against what were criticized as anti-Latino policies of Gov. Ronald Reagan of California.

Other photographs document government pushback against this activism, including police surveillance, brutality and harassment. Some depict the activities of everyday life, from a woman styling hair in a beauty salon to a boy shining shoes. And others portray the robust cultural expression of the Mexican-American community, from posters and graffiti to murals and theatrical performances.

In the end, these photographs helped shape the collective identity and political consciousness of the Chicano community. By making these images available to fellow members of the Chicano Press Association, as well as to mainstream and underground outlets, La Raza challeneged media stereotypes by showing a self-possessed, engaged and resilient people. “As citizen-photojournalists on the La Raza staff, we would arm ourselves with cameras to shoot the day’s events,” Mr. Garza wrote. “We were dedicated to telling our side of the story, since the mainstream media would only tell it in a negative light.”

Today, when political leaders — not to mention neo-Nazis, too — appeal to xenophobia, nationalism and white supremacy, these photographs have continued relevance. Projects like La Raza remind us of the complex history and nuanced identities of many Americans, a point exemplified by the newspaper’s dual inaugural issue. Its two editions — dated Sept. 4 and Sept. 16, 1967 — were meant to commemorate the founding of Los Angeles and of Mexican Independence Day, in that order.

Ms. Davalos argues that the La Raza exhibition — and the vast archive that is its source — can help us to better understand a rich visual history that has yet to be fully recognized.

“I imagine we will find our Gordon Parks, our Manuel Álvarez Bravo, our Dorothea Lange within this archive and exhibition,” Ms. Davalos said. “We will also find the ways in which Chicano photographers organically envisioned what they called community, what they called politics. We have yet to determine the trends, the themes, the visual accomplishments and the ways these photographers were pushing boundaries.”

Source: New York Times