By Gabriel San Ramon | LA Times | APR. 14, 2022 | Photo from the archives of Chapman University

Before influenza cases ravaged through Orange County in the fall of 1918, a battle brewed at the Santa Ana Board of Education over Mexican students.

Trustees reneged on their promise to build a Mexican school in time for the new academic year. Meanwhile, the number of Mexican students at Lincoln School had grown by more than 100, an untenable situation for segregationists there who led the charge.

According to Board of Education minutes, the board looked at possible Mexican school sites as early as July and moved to purchase two lots but ultimately found construction too costly.

Supt. J.A. Cranston considered moving two Mexican classes into a Lincoln Elementary “shack” previously used as a changing room for student athletes. The temporary compromise also included separate recess periods so the playground wouldn’t be integrated.

Lincoln’s PTA pushed back. Its president decried that past segregation of Mexican students at Washington School in 1913 had ended and presented a resolution before an Aug. 9, 1918 school board meeting.

“We protest vigorously against any plan that will mean the location of any Mexican classes upon the Lincoln school grounds, whether in the main school building or in any other building,” it read. “The placing of a Mexican makeshift school upon the Lincoln grounds would be a rank injustice to our school, our teachers and our children.”

The resolution passed.

Trustees directed staff to open bids on materials to build a Mexican school and vowed by vote to segregate “sub-normal pupils in the grammar schools.”

But the opportunity to do so wouldn’t present itself until November when influenza cases surged during the 1918 pandemic’s deadly second wave.

By then, Santa Ana became one of the last Southern California cities to shut down gatherings at churches, pool halls, theaters and libraries by way of an Oct. 19 public health order; Cranston closed the schools for a month.

The Mexican question remained, especially as trustees considered how to safely reopen classes before Christmas.

Dr. J. I. Clark, Santa Ana’s health officer, joined various PTA groups in urging that Mexican students be segregated on account of influenza. He even suggested that school nurses conduct flu inspections at Mexican homes.

The board ceased sewing, cooking and manual training classes at a building on Church Street, which is now Civic Center Drive, in favor of repurposing it as a makeshift Mexican school until a permanent solution could be found.

On Nov. 18, classes resumed, but Mexican students largely stayed home.

“It is very likely that a vast majority of the Mexicans were not aware of the reopening this morning,” the Santa Ana Register reported. “Few of them read the daily papers and probably will not learn of the resumption of school until it is passed by word of mouth.”

Segregation continued in Santa Ana from that morning until an appellate court ruling in Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al 75 years ago today, drove a final legal stake through the heart of the state’s Mexican schools.

The board did consider the legality of segregation during a Jan. 13, 1919 meeting after classes resumed the week before. Trustees invited Santa Ana City Atty. George H. Scott to offer an opinion on the matter.

He noted that state law allowed Native American, Chinese and “people of Mongolian descent” to be segregated from their white counterparts at school.

“There seems to be no provision empowering Boards of Education to maintain separate schools for Mexicans or other nationalities,” Scott, a former judge, opined. “It is entirely proper and legal to classify [students] according to the regularity of attendance, ability to understand the English language and their aptness to advance in the grades to which they shall be assigned.”

Long before the Mendez case, Mexican Americans belonging to the Pro Patria Club immediately opposed the segregation of their children at the meeting and filed a petition against it as an unlawful act.

The Register reported that parents had been whipped up by the “thoughtless agitation” of a Mexican newspaper in Los Angeles, which stressed the pandemic roots of discrimination.

“Excellent progress has been made by the children at the Mexican school,” Cranston was quoted as saying in the Register. “The children themselves like it. They don’t want to go back to the other schools.”

The superintendent cited a survey by teachers where it was claimed only one out of 116 Mexican students wanted to return to their former schools in sharp contrast to their parents’ demands.

“While the influenza epidemic caused the closing of the American schools,” Cranston continued, “a number of Mexican children who were backward in their classes were told that if they wanted to do so during the vacation they could go to the Mexican school.”

Armed with the city attorney’s opinion, the board dismissed the Pro Patria Club’s petition and voted to continue working on permanent Mexican schools “especially for the great benefit to the Mexican children.”

Some parents refused to send their children to the Mexican school on Church Street.

Venecio Ramirez and Francisco Bielman were given suspended sentences for their children’s truancy. A Pro Patria Club official presented a signed statement urging compliance in the community. Three more warrants were issued against Mexican parents, but their children reported to school before being arrested.

Later that year, the board purchased two sites for future Mexican schools — one at Stafford and Logan streets and the other at Second and Santa Fe streets.

In June, trustees accepted the bid of E.W. Smith to construct a permanent Mexican school; he would later build the southwest-style Floral Park home of Ralph Smedley, the founder of Toastmasters, in 1925.

Santa Ana expected its white schools to open on Sept. 10 while construction of Mexican school buildings would be completed by Oct. 1.

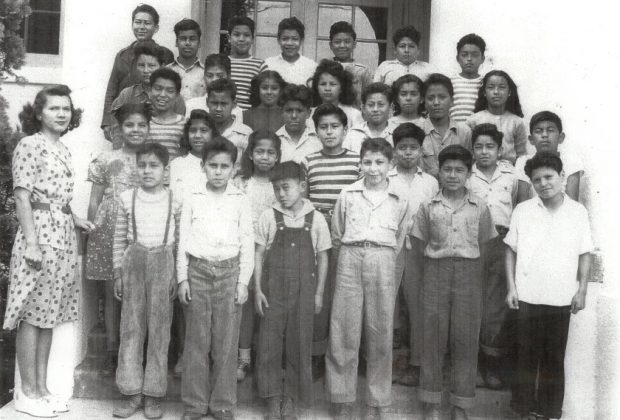

The late Virginia Guzman was one of many students who attended Fremont, a Mexican school in Santa Ana. Along with her husband, William, she didn’t want the same for their son, Billy Guzman. But the district denied their request that he be allowed to attend Franklin School along with white students.

In 1945, William Guzman joined the Mendez case alongside Gonzalo Mendez, Thomas Estrada, Frank Palomino and Lorenzo Ramirez. The class-action suit represented 5,000 Mexican school students in the Santa Ana, Garden Grove, Westminster and El Modena school districts.

Mendez and Palomino’s children had, at one time, also attended Fremont.

U.S. District Court Judge Paul J. McCormick found Mexican schools to be illegal in siding with the plaintiffs. Santa Ana was one of three districts to appeal but on April 14, 1947, an appellate court unanimously upheld McCormick’s ruling.

In June, the Santa Ana Board of Education voted to discontinue their legal fight.