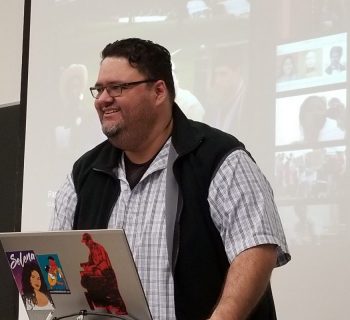

By Alfonso Gonzalez Toribo and Jennifer R. Najera | Press-Enterprise | APR. 16, 2022 | Photo from UC Riverside

The Inland Empire has lost an important scholar and activist. Armando Navarro, a retired UC Riverside ethnic studies professor, passed away from a heart attack on March 25, 2022. He was 80.

Navarro, professor emeritus in the Department of Ethnic Studies at UCR, was a trained political scientist — he obtained a Ph.D. in political science from UCR in 1974. He became the first full-time Chicano Studies faculty member in the Department of Ethnic Studies when he began teaching at UCR in 1992; he retired in 2015.

Navarro was an organic intellectual — a person with natural ties to a social group, who articulates the interests of this group, and gives it self-awareness. He used his gift for analysis and position as a professor for educating, leading, and organizing Latinos in the Inland Empire and beyond.

Navarro played a critical role on campus and in the community. During his academic career, he published seven books and completed an eighth one before his death. His early works looked at the origins, growth, and eventual collapse of Chicano Movement organizations such as the Mexican American Youth Organization and the Raza Unida Party. In the mid 2000s, he focused on Mexican American political strategy and immigration politics. His latest works developed a critique of global capitalism: its social and economic polarizing effects and its implications for Mexican and Latino politics in the 21st century. Navarro approached this work as a political scientist drawing from historical and autobiographical frameworks and analyses.

Born in 1941 and raised in what is now Rancho Cucamonga — then a small Mexican barrio — Navarro witnessed mass deportations, repression for speaking Spanish, and blatant racism. He was a U.S. Army lieutenant and one of the founders of the Raza Unida Party in California. As early as the1980s he organized against Border Patrol raids in the Inland Empire, also mounting counter protests when the KKK marched in Fontana during that same decade. In the early 2000s he confronted the Minutemen, a vigilante Border Patrol group whose reach spanned beyond the border into the Inland Empire. The Minutemen, along with other ultra-right-wing groups, targeted and threatened Navarro, yet he never backed down.

Navarro was a tireless defender of Latino and immigrant rights, organizing and mobilizing both students and community members. Perhaps most notably, Navarro organized a national summit in Riverside in 2006, when the Sensenbrenner bill, which among other extreme measures would have made it a felony to be undocumented, passed in the 109th House of Representatives. Various immigrant rights leaders from Arizona, Illinois, Texas, New York, and California convened to discuss and strategize a response to the bill. At this summit, movement leaders ultimately planned the immigrant rights protests for the spring of 2006, which became the largest peaceful marches of their kind across the United States.

Without the use of social media, government, or corporate funding — and without abandoning the critical ethos that he carried since his days as a Brown Beret, Navarro brought to bear critical leadership to articulate a national platform for unity and action among Latinos during that crucial moment.

Navarro was also a Chicano internationalist. He organized several delegations to Cuba and Venezuela. During the Zapatista uprising in Mexico in the 1990s, Navarro organized a delegation of UCR students and Inland Empire leaders to meet with Sub-Comandante Marcos.

Navarro managed to develop this brand of politics in the 1990s when the Inland Empire was a different place. The population was nearly half of what it is today. It was nearly 70% white, Republican, and an epicenter for anti-immigrant violence. It was a time too when there were few Latino elected officials and when students walked out of area high schools to protest Proposition 187, another anti-immigrant effort to forbid undocumented residents from accessing social services.

Latinos today make up over 50% of the Inland region. Chicano movement organizing tactics have given way to the more traditional forms of political action that Navarro was increasingly critical of. Latino elected officials are now part of the landscape from the Coachella Valley to Jurupa Valley. Autonomous grassroots organizing has mostly given way to nonprofit organizations and foundation driven activism.

Though he was often misunderstood and sometimes shunned by the new generation of Latino professors, Navarro left an important legacy. He bridged his scholarly publications with community work as envisioned in the philosophical documents that guided Chicano Studies Programs. He was pivotal in politicizing the generations that proceeded him and set the groundwork for the Inland Empire to become the emerging heartland of Latino Southern California. Inspired by him, many of his students and young activists have become journalists, lawyers, professors, and elected officials in the region.

Navarro’s legacy is firmly sealed as the Inland Empire’s most important Chicano leader of his generation.