By Nigel Duara and Cindy, L.A. Times ~ November 20, 2015

To its southern neighbor, the United States once represented hope, safety and prosperity. But with the effects of the Great Recession still lingering and tougher enforcement along the U.S. border, fewer Mexicans see a reason to leave their homeland.

“There isn't much work because the economy there is still bad,” said Eleuterio Hernandez Hernandez, who for 26 years made frequent unauthorized trips to the U.S. from San Bartolome Quialana, a small city in the state of Oaxaca in central Mexico.

Though the U.S. economy continues to rebound, that hasn't always translated to into low-skilled jobs for border crossers. “There is no work for us immigrants,” he said.

At 51, Hernandez Hernandez, has stopped traveling north for work. “I'm too old and it's too difficult.”

Workplace raids by immigration agents, nose-diving birthrates at home and the economic slowdown north of the border have convinced 47% of Mexicans surveyed that life in their native country is as good or better than what would await them if they crossed into the U.S., according to findings released Thursday by the Washington-based Pew Research Center.

“I would not say that Mexico has more of a pull,” said study author and Pew research associate Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. “But the United States isn't as attractive.”

The report echoes studies that had recorded drops in illegal immigration, but it delves into the reasons driving the trend and contrasts the drop with the number of Mexicans who leave the United States.

According to census numbers from the U.S. and Mexico, since 2005 Mexican nationals have begun to leave the U.S. in greater numbers than at any point in history, and the largest share of those who return to Mexico are immigrants who had been in the country illegally.

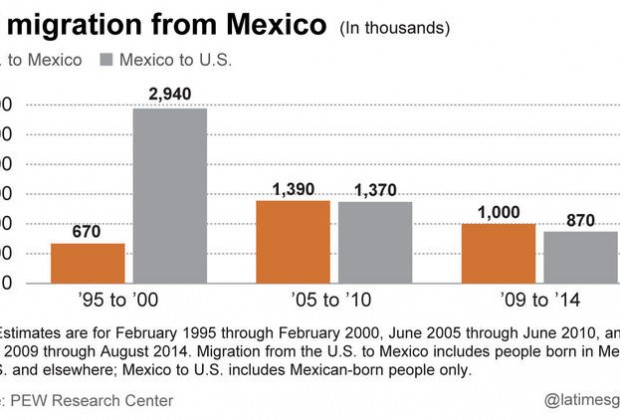

The number of people leaving the U.S. began to fall off in 2010. By 2014, fewer Mexican nationals were leaving the U.S. than a decade earlier, but even fewer were entering the country from Mexico. The result, Gonzalez-Barrera argues, is the first modern instance of the migration scales tipping: More Mexican nationals are leaving the U.S. than the number of Mexicans entering the country.

“We haven't seen that since the 1930s,” Gonzalez-Barrera said.

Sneaking into the United States was easier in the past. When Hernandez Hernandez slipped into Los Angeles from Tijuana in 1981, it cost just $300. He took jobs as a cook in West Los Angeles and Santa Monica. In San Bartolome Quialana, newer brick houses compete with traditional adobe houses, and donkeys share the road with cars amid Oaxaca's low foothills. Hernandez Hernandez's modest storefront, called Abarrotes California, or California Groceries, is a testament to the money he earned in the U.S.

But then, like a healthy percentage of Mexicans polled by Pew, he began to feel as though the tightened border security and dampened economic opportunities north of the border made the increasingly costly crossings less appealing. A smuggler in 2005 asked $2,000 to get him across the border.

In 2007, with work drying up and Hernandez Hernandez missing his family, he returned to San Bartolome Quialana and then stayed put.

To those who advocate for more stringent immigration standards, the report's main assertion — that there are conclusively more Mexicans leaving the U.S. than entering the country — is a red herring and fails to paint an accurate picture of problems along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“The point of this report and the way it'll be used is there's no more concern about the border, Republicans are idiots and the issue has faded,” said Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which favors restrictive immigration policies. “What it really shows is that a narrow focus on the southern border is incomplete.”

A border fence cuts through the desert that separates Nogales, Ariz., from Mexico. A new report says migration from Mexico has dropped while more Mexican in the U.S. have returned to their homeland. (John Moore / Getty Images)

The report focused on migration of Mexicans, not other nationalities. Last year and this fall, U.S. immigration authorities detected an uptick in illegal immigration from Central America. The number of immigrants from China and India rivals that of Mexicans, and nearly all illegal immigration from those countries is the result of visa overstays.

Krikorian said that means it's time for a new approach to immigration enforcement that focuses on tracking down visa overstays and enforces illegal immigration checks at work sites.

Mexico has not become more alluring, Gonzalez-Barrera said, despite the presence of more jobs in the country — and fewer births means fewer people in the labor pool. But the image of the U.S. has been tarnished among Mexicans, according to opinion polling cited by Pew.

About half of all adults in Mexico still think that those who have left for the United States lead better lives than those left behind, but the growing share who don't see much of a difference is the key to understanding the most recent cycle of immigration.

In the 1990s, Mexico was burdened by an economic downturn, and a tremendous number of people born in the 1970s were finally entering the labor pool. Seeking a way to earn money, children and adults younger than 30 made up 50% of immigrants into the U.S. from Mexico in 1990, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and its American Community Survey.

The North American Free Trade Agreement also led Mexicans out of their country's farm sector, Gonzalez-Barrera said, and the U.S. border was so porous that there was little disincentive to stay in Mexico. “Anybody who could come across could get in,” she

said.

In the 2000s, the U.S. began to change its border policy. It now criminalizes people who cross the border more than once. Highly publicized workplace raids that rounded up scores of unauthorized workers — for example, at a meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa — reinforced the idea of a more watchful federal government.

From 2005 to 2009, census data from the U.S. and Mexico cited by Pew showed about the same number of Mexican nationals entering the country as leaving.

Those who are still coming to the U.S. are doing so for the money, Gonzalez-Barrera said.

“U.S. wages are still attractive to migrants,” she said. “There is still much more to be earned here than in Mexico.”

The Mexican National Survey of Demographic Dynamics found that the pull of family factors most into Mexicans' desire to return home. The survey, conducted in 2014, found that 6 in 10 Mexicans who moved to the U.S. after 2009 and returned to Mexico before 2014 said they returned to reunite with family or start a family of their own.

Far smaller shares said they had been deported (14%) or returned to look for work (6%).

More Mexicans leave than enter USA in historic shift

By Alan Gomez, USA TODAY ~ November 19, 2015

For the first time in more than four decades, more Mexican immigrants are returning to their home country than coming to the United States, according to a report released Thursday…

For the first time in more than fou

r decades, more Mexican immigrants are returning to their home country than coming to the United States, according to a report released Thursday.

From 2009 to 2014, an estimated 870,000 Mexicans came to the United States while 1 million returned home, a net loss for the United States of 130,000, according to the report from the Pew Research Center. That historic shift comes at a time when immigration has become a contentious focal point in the 2016 presidential race, as Republicans and Democrats argue over how best to modernize the nation's immigration system.

Mark Hugo Lopez, director of Hispanic research at the center, said the net decline in Mexicans was driven by the Great Recession in the United States that made it harder to find jobs, an improving economy in Mexico and tighter border security.

In coming years, he said, the number of Mexicans may increase again if the U.S. economy continues to improve. But steady growth of Mexico's economy and tighter controls along the southwest border mean the United States won't see another massive wave of legal and illegal immigration like it did in recent decades, when the number of Mexican-born immigrants ballooned from 3 million to nearly 13 million, he said. "The nature of immigration itself is beginning to change," Lopez said. "It looks likeMexican migration is at an end."

The reversal of Mexican migration doesn't mean that the United States is seeing fewer immigrants overall, just that their countries of origin are changing.

The United States has seen a record number of Central Americans fleeing violence in the past few years, straining the country's ability to process their requests for asylum. In addition, Lopez said, immigrants from China, India and other Asian nations are coming as students and high-tech workers. Eventually, Asians will become the dominant share of the immigrant population, he added.

Roy Beck, president of NumbersUSA, a group that advocates for lower levels of legal and illegal immigration, said it would be a mistake to view the slowdown in Mexican migration as th

e end of the United States' immigration boom. He said the country continues to see a massive stream of foreign workers entering on work visas, sometimes overstaying those visas and sometimes sponsoring their entire families to come with them.

He said those workers, combined with their relatives who can later join them in the United States through the country's generous family migration rules, represent constant job competitors for underemployed Americans.

"The effect on the American worker is pretty much the same, whether they're coming from Mexico or anywhere else," he said.

The slowdown in Mexican migration also means that the profile of Mexican-born immigrants in the United States has changed dramatically. They have become more settled in the U.S., are older on average and have completed high school and college at higher rates. For example, 76% of Mexican-born immigrants in the United States had not completed high school in 1990. By 2013, 42% had completed high school and 18% had started or graduated from college.

Among the other findings in the report:

- Only 14% of the 1 million Mexicans who returned to their country since 2009 said they did so because they were deported. A majority said they returned of their own accord, with 61% saying they did so to reunite with family.

- Mexicans have fewer ties to people living in the United States. In 2007, 42% of Mexicans surveyed by Pew said they kept in contact with friends or family in the United States. In 2015, that figure had fallen to 35%.

Study Finds More Mexicans Leaving the US Than Coming

By ELLIOT SPAGAT, AP ~ November 19, 2015

San Diego (AP) -- More Mexicans are leaving the United States than migrating into the country, marking a reversal of one of the most significant immigration trends in U.S. history.

A study published Thursday by the Pew Research Center said a desire to reunite families is the primary reason Mexicans go home. A sluggish U.S. recovery from the Great Recession also contributed. Meanwhile, tougher border enforcement has deterred some Mexicans from coming to the United States.

Pew found that slightly more than 1 million Mexicans and their families, including American-born children, left the U.S. for Mexico from 2009 to 2014. During the same time, 870,000 Mexicans came to the U.S., resulting in a net flow to Mexico of 140,000.

A half-century of mass migration from Mexico is "at an end," said Mark Hugo Lopez, Pew's director of Hispanic research.

The finding follows a Pew study in 2012 that found net migration between the two countries was near zero, so this represents a turning point in one of the largest mass migrations in U.S. history. More than 16 million Mexicans moved to the United States from 1965 to 2015, more than from any other country.

"This is something that we've seen coming," Lopez said. "It's been almost 10 years that migration from Mexico has really slowed down."

The findings counter the narrative of an out-of-control border that has figured prominently in U.S. presidential campaigns, with Republican Donald Trump calling for Mexico pay for a fence to run the entire length of the 1,954-mile frontier. Pew said there were 11.7 million Mexicans living in the U.S. last year, down from a peak of 12.8 million in 2007. That includes 5.6 million living in the U.S. illegally, down from 6.9 million in 2007.

In another first, the Border Patrol arrested more non-Mexicans than Mexicans in the 2014 fiscal year, as more Central Americans came to the U.S., mostly through South Texas, and many of them turned themselves in to authorities.

The authors analyzed U.S. and Mexican census data and a 2014 survey by Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography. The Mexican questionnaire asked about residential history, and found that 61 percent of those who reported living in the U.S. in 2009 but were back in Mexico last year had returned to join or start a family. An additional 14 percent had been deported, and 6 percent said they returned for jobs in Mexico.

Still, it's this lack of jobs in the U.S. — not family ties — that is mostly motivating Mexicans to leave, said Dowell Myers, a public policy professor at the University of Southern California. Construction is a huge draw for young immigrants, but has yet to approach the levels of last decade's housing boom, he said.

"It's not like all of a sudden they decided they missed their mothers," Myers said. "The fact is, our recovery from the Great Recession has been miserable. It's been miserable for everyone."

Also, Mexico's population is aging, meaning there's less competition for young people looking for work there. That's a big change from the 1990s, when many people entering the workforce felt they had no choice but to migrate north of the border, Myers said.

While the U.S. economic recovery is sluggish, Mexico has been free in recent years from the economic tailspins that drove earlier generations north in the 1980s and 1990s. The peso is relatively stable, inflation is manageable, and while many parts of Mexico suffer grinding poverty and violence, others -- especially in the more industrial northern half -- have become thriving manufacturing centers under the North American Free Trade Agreement, producing cars, airplanes and other heavy equipment.

"The main reason for my return is family," José Arellano Correa, a 41-year-old Mexico City taxi driver who came back from the U.S. in 2005. "I could help them while I was there, but family comes before money."

Mexicans who remain in the U.S. are more settled than before, Pew said: Their median age was 39 years in 2013, compared to 29 in 1990. More than three in four had been in the U.S. for more than a decade, compared to only half in 1990.

Another telling statistic: 35 percent of adults in Mexico say they have friends or relatives they regularly communicate with or visit in the U.S., a Pew survey this year found. That's down 7 percentage points from 2007.

Guadalupe Romo, 49, has lived in Fresno, California, for 26 years and has no plans to leave.

"We have our life here," she said at Fresno's Mexican consulate. "There's no point in going back to Mexico."

###

Associated Press writers Scott Smith in Fresno, California, and Alberto Arce in Mexico City contributed to this report.