By: Edward P. Lazear, NBER Working Paper No. 23548 ~ Issued in June 2017

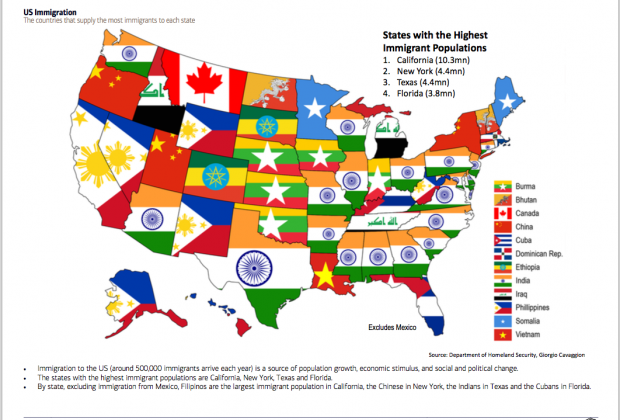

Algeria, Israel, and Japan, along with over one hundred other countries, are sources of immigrants in the United States. Try the following thought experiment: Rank those three countries’ immigrants, highest to lowest, by educational attainment. The ranking is Algeria, Israel, and Japan. Surprised? Consider an additional fact: Algerians make up .0004 of immigrants, Israelis comprise .003 of our immigrants whereas about 1% of immigrants are from Japan. The largest origin country of immigrants is Mexico, accounting for 27% of the immigrant population in the U.S. Mexican immigrants rank 134th out of 136 in educational attainment, as compared with Algerian immigrants who rank 25th. Yet, average education attainment in Mexico is 8.5 years, whereas in Algeria it is only 7.6 years. The group with the highest educational attainment are those from the former Soviet Union, who make up .001 of all immigrants.

The attainment of immigrants in the U.S. varies greatly by country of origin. Average educational attainment by country of origin ranges from a low of 9 years of schooling to a high of 16 years. Similarly, average annual earnings by country of origin ranges from about $16,000 to $64,000. Not surprisingly, the correlation between these two measures of attainment across 134 origin countries is 0.7. Additionally, two of the largest sources of US immigrants are at both extremes, with Mexico’s migrants to the US having a mean educational attainment of 9 years, whereas India’s migrants to the US have a mean of 16 years. Contrast that with the fact that the average educational level in Mexico is almost twice that of the average educational attainment in India. What explains these immigrant attainment differences across origin countries and the counterintuitive patterns?

Because the US admits as immigrants only a small fraction of most origin countries’ populations, almost every country has a large enough group of highly educated people from which the US could draw its immigrants. Many of these individuals might be willing to move to the US if admitted, which implies that the average educational attainment of immigrants from any origin country depends in large part on whom the US is willing to admit. The more selective is immigration policy, the higher is the educational attainment of the group.

Few Algerians ever obtain permission to come to the United States and those who do tend to be highly educated. In contrast, most Mexican immigration is based on family reunification. Although family reunification is a worthy goal, a selection system based primarilyon that factor will not generate a population of immigrants with the highest levels of education.

Rather than modeling US immigration as driven by supply considerations such as the wage that an individual can earn in the US relative to what he or she earns at home, the focus here is on the rationing mechanism. Most models of immigration treat migrants as if they are mobile labor, moving from one sector to another freely, without any constraints on the migrant imposed by policy.1 These models have served analysts well in considering who chooses to come to the US, but they are less well-suited to describing the composition of the immigrant population and its educational attainment and wage levels.

Supply factors that would determine who would move from one occupation or industry to another in an open economy with free mobility are de-emphasized (although not ignored) here because would-be immigrants do not have free choice over whether they are admitted to a country. Models that assume that individuals are free to choose the country to which they migrate omit an important consideration, namely, that immigration slots are rationed in many countries and in the United States, in particular. For example, between 2009 and 2014, approximately 1 million individuals per year were granted permanent resident status. In each of those years, there was a large number of applicants who were in the queue for resident status, equaling about four times as many as the number granted permanent residency.2 There is excess supply of immigrants, even by measures of those who apply. There are surely many more who would apply if they thought they would be admitted, but decline to do so because the likelihood that their application will succeed is too low.

To explain the attainment of immigrants, another extreme approach is adopted, albeit a caricature of the true situation. The analysis here emphasizes rationing. It is assumed that anyone who is offered admission to the US from another country accepts that offer and migrates to the US. The shape of the education distribution in the origin country, the country’s population, and importantly, the target immigrant number from that country determine the composition and attainment of immigrants in the US. Supply considerations enter primarily by affecting the educational distribution that prevails in the immigrant’s country, but are also relevant in providing a rationale for the assumption that the most talented individuals from each origin country are selected by the US.3

Although the point of this analysis is not unique to the United States, the focus is the US because the assumption that the selection filter, rather than supply considerations, are paramount is more applicable to the US than to most other countries. The excess supply of migrants to the US means that the rationing rule is a key factor in determining the nature of immigrants in the US.

The model, which implies that three and only three variables should determine educational attainment does well. In the US, 73% of the variation in immigrant educational attainment is explained by the variables of interest in the model, namely the number of immigrants in the US, the population of the origin country, and the mean level of educational attainment in the origin country.

Figure 1 illustrates the main argument. Consider two countries, 1 and 2, with equal population sizes and with educational distributions as shown. Country 2's distribution is a rightward displacement of country 1's distribution.

Suppose that the US were to decide that 3% of its immigrants will come from country 1, but that 30% will come from country 2. If the US also allows only the most educated immigrants in first from each country, or alternatively, if the most educated in each country are most attracted to the US or most able to negotiate their way through the immigration process, then the upper tail of each distribution will end up migrating to the US. In this case, because the US targets 3% from country 1 and 30% from country 2, the minimum cutoff level of education in each country is A1* and A2*, respectively. Note that the educational cutoff level for country 1, the lower education country, is considerably above that for country 2, the higher education country, because so many more are being admitted from country 2. Given the cutoffs and the underlying distributions, the average level of education among immigrants from country 1 and country 2 are A1 and A2. The educational attainment of immigrants from 1 exceeds that from 2, i.e., A1 > A2 , even though country 1's education level at home is below that of country 2 at home.

Of course, this is not a necessary outcome. It depends on the amount by which country 2's education level dominates country 1 and in particular on the number of immigrants that the US admits from each of the two countries. But figure 1 illustrates that other things equal, the smaller the proportion of immigrants in the US who come from a country, the higher is the expected level of education of immigrants in the US who are supplied by that country.

➡️ Download the Full Report Here ⬅️

Source: http://www.nber.org/papers/w23548

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications.

© 2017 by Edward P. Lazear. All rights reserved.

Why Are Some Immigrant Groups More Successful than Others?

Edward P. Lazear

NBER Working Paper No. 23548

June 2017, Revised July 2017

JEL No. F22,J01,J15,J61,M5