By Krystal A. Sital, The New York Times Magazine ~ December 2, 2016

On that particular evening back in 2003, my parents were in the car together returning home from work — my mother was a babysitter, my father an electrician — when they noticed three men in suits reading the labels on the mailboxes in front of our building. This was on the urban streets of New Jersey, against a backdrop of dilapidated buildings, and they immediately assumed who it was.

“Go in your bedroom and hide,” my mother hissed over the phone. “Immigration is here. Do not open the door.” My younger sister, Kim, was only 12, and I was 16, a junior in high school. When I relayed the message to her, we both grinned. Our family had a dark sense of humor, and even though we were residing in the United States illegally, this sounded like just the kind of prank she would play on us.

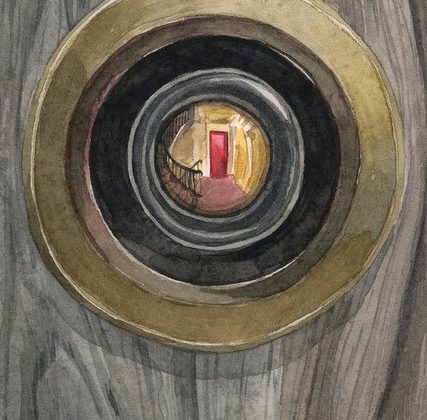

“Krys,” she said, “this is not a joke! I am sitting outside with your father. They are going upstairs right now. Hide!” Her voice was too serious, too worried. Not a tremor of a laugh vibrated in her words. So I shut my sister in our bedroom, turned off all the lights and locked the windows. We lived in a third floor walk-up in Bayonne. It would take them a couple of minutes to get up there, so I stood behind the door of our apartment and peered through the peephole. I could hear footsteps on the wooden stairs — not the weary ascension of the old Egyptian lady and her husband who lived across the hallway or the skip of the little Puerto Rican boy below us or the cheerful whistle of the African-American woman on the first floor.

It was when the tops of their heads floated above the railing that I really believed my mother’s words. Having gone through the motions of locking the apartment down, I was still hoping it was all an elaborate gag. I felt the unlawfulness of our status in this country acutely. As far as I knew, they could, and had every right to, remove us from our apartment and send us back to our country, Trinidad and Tobago.

The three came one behind the other down the narrow corridor. I trapped a breath in my chest and stepped away from the door just as the one in front raised a fist to rap his knuckles where my face had been.

I had heard stories of immigration officers not even bothering to knock but kicking down the door and sweeping every family member into an unmarked white van. I was terrified that would happen now. My back was against the wall of the kitchen, and I wanted so desperately to close the short distance between me and the locked door of my bedroom, but I knew a creaking board could signal our presence. I yearned to be next to my sister, our shoulders touching and heads inclining toward each other in our dark closet. Instead I stood next to the door, letting air out of my chest one miniature puff at a time.

Although the apartment’s imperfections were many, from the lack of space to the falling plaster, we called it home. My mother sewed curtains, glued wallpaper and repaired the ceiling; my father rebuilt cupboards, ran new lights and retiled the bathroom. Under normal circumstances, these updates would fall on the landlord’s shoulders, but we flew under the radar, so it was done on our own.

Each knock on the door sent a cold stab through my body. I clutched my belly, feeling the sharpness of my nails, something to ground me. Having finally succeeded somewhat in assimilating into American culture, we weren’t sure what would happen if we were sent back. My parents brought us to the United States knowing this could happen once our visas expired. We had abandoned the tangerine skies of the islands for New Jersey at a violent time in our country. My father, a police officer there, believed it was worth the risk to live in the safety of the States.

At one point, I heard the men step away, and I braced myself for the crashing of the door. But all I heard was the familiar creaking of stairs as they descended. I listened till the door of the building slammed closed behind them before I checked the peephole and released a trembled breath. An empty corridor.

I dug my sister out of our room, held onto her and cried until our parents came and gathered us up. We left the apartment, but there was really nowhere else for us to go, so we returned that evening. For a long time we waited in fear for them to come back. We were always cognizant of our surroundings, always vigilant in a way that was just below the surface.

Eventually we would gain legal status, and over time the fear was layered over by everyday life — worrying about grades, fencing practice, the attention of boys — until a knock at the door was finally transformed into a joke. “Be careful,” my mother said, “it might be Immigration.” The fear was still there, but we had to move on.