By Juan Pablo Murra | North Capital Forum | 2023 Photo by Conecta TEC MX

Introduction

International trade and globalization have brought the world closer together, offering opportunities for increased connectivity. Technology is a significant catalyst for regional and international development. The exchange of goods, services, and capital across borders has created unity among countries and the global community. However, what nurtures symbiotic relationships is the interconnectivity of people. Migration has become a significant driver of growth, playing a crucial role in addressing skill gaps, labor shortages, and the challenges posed by aging populations, particularly in the global north. Unfortunately, most countries do not have adequate policies to attract and retain talent.

Moreover, international student migration is a means for countries to attract talent and establish systems for skills formation to meet future employment needs. Student mobility across the globe yields numerous advantages. Migrant students tend to benefit from higher wages without detrimental effects on most native workers. Also, they can foster economic growth in their home and host countries. Implementing an open visa policy can serve as an effective strategy to attract more high-quality students (Chevalier, 2022). As of 2019, the number of students traveling abroad for educational purposes was over 5 million resulting in a direct annual expenditure of 196 billion dollars. It is projected that by 2030, this figure will rise to 8.95 million students (about half the population of New York) enrolled in foreign universities (Holon I.Q., 2023).

North America is recognized as one of the world's most economically dynamic regions. Together, the three countries generate 28% of the global GDP (Gross Domestic Product)(2), despite representing only 6.3% of the world's population. Furthermore, in terms of international trade, these countries accounted for 13% of total trade (3) and 29% of global foreign direct investment flows in 2021 (4). Canada, Mexico, and the United States of America have a modern history of 30 years of economic integration since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Following the renegotiation of NAFTA, implementing the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) has sustained economic prosperity, regional integration, and enhanced interconnectedness among the three countries.

However, this initiative has failed to generate associated processes to accelerate critical areas of competitiveness, such as fostering greater convergence in higher education and implementing more effective strategies to promote and attract talent within the region. In 2020, only 75,271 students from North America migrated within the region for educational purposes (UNESCO, n.d.), representing a mere 1.2% of the total, according to Holon IQ’s report of global student mobility. In an effort to foster greater collaboration in education throughout North America, it is crucial to consider the differences in strength and characteristics of higher education among its members.

Furthermore, with the labor and talent shortages impacting the region, along with the accelerated aging population in Canada and the United States–albeit at a slower pace in Mexico–it would be natural to expect efforts that seek a better interconnection of talent to address these challenges. Additionally, events such as the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the U.S. and China tensions in trade and technology, have led to an important shift in the global supply chain. The region’s relevant position in global trade has been impacted by this new readjustment, known as near-shoring, in which global companies have sought to relocate their manufacturing plants to closer countries (Aspe, 2023).

Given these new circumstances, the imperative for the region is to focus on talent development and the establishment of a system for skills formation. Nevertheless, a clear pathway for creating actions and strategies for this purpose seems to be lacking. This paper aims to provide clarity on the challenges the region faces in increasing the flow of skilled and talented individuals while shedding light on potential paths that can foster a more symbiotic relationship for economic and human capital growth.

The Challenges of Student Mobility in North America

International student mobility in the region does not seem as prominent as expected. For the 2019-2020 school year, according to data from the Institute of International Education (IIE), the leading destination for Mexican students–exchange, undergraduate, or graduate programs–was Spain, with 4,352 students. That same year, the United States ranked as the second destination with 1,884 students, while Canada ranked fourth with 1,448. On the contrary, in the case of Canadian students, the leading destination for studying abroad was the United States (26,524 students). The United Kingdom ranked as the second country destination (6,760). The United Arab Emirates was third, and Australia fourth. Mexico was the fifth country destination, with a total of 2,184 students.

From the inbound mobility perspective for the 2020-2021 school year, the major countries sending students to Canada were China and India (IIE, 2023). Indian students have grown during the last decade, from 31,665 in 2012-2013 to 217,410 students in 2020-2021. On the other hand, 53% of international students in the United States come from India and China. The growth in the flow from these two countries is not as remarkable as in the case of Canada, but it is noteworthy. In the same period, mobility from India and China to the United States increased by 73.2% and 34.7%, respectively.

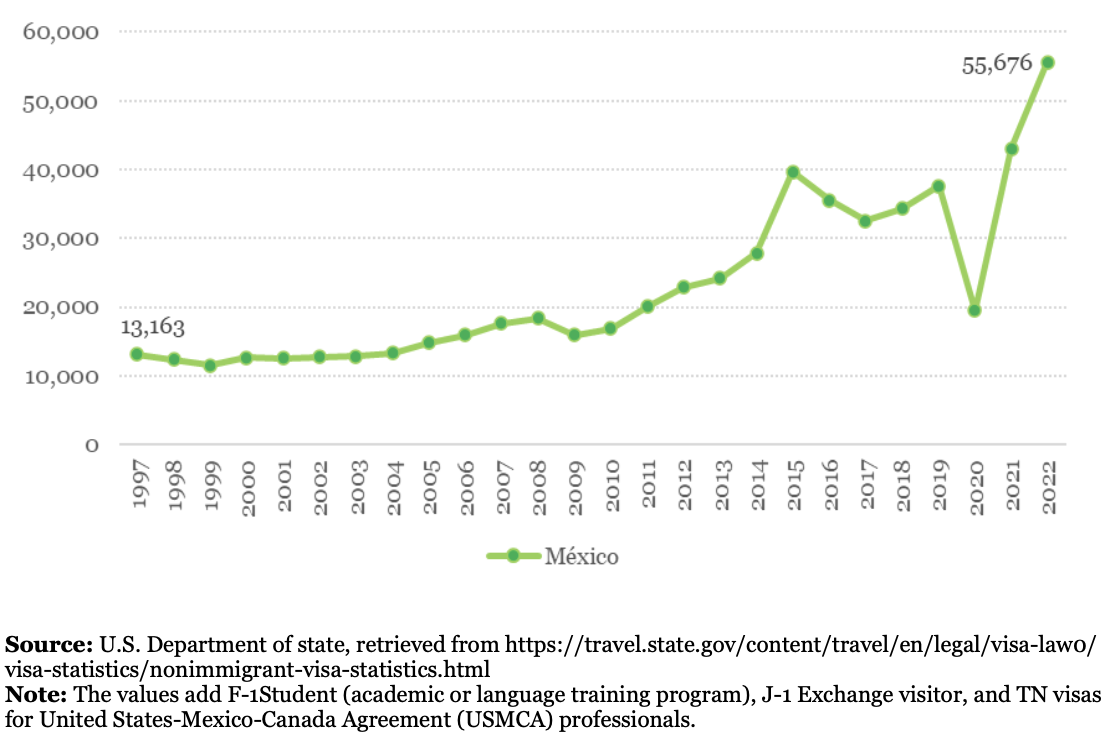

A strategy for talent attraction for the U.S. for intraregional student mobility could be based on two feasible options: TN (nonimmigrant) visas, contemplated within the USMCA, and student (F1 and J1) visas. The nonimmigrant NAFTA, and now USMCA, Professional (TN) visa allows citizens of Canada (5) and Mexico, as NAFTA professionals, to work in the United States in prearranged business activities for U.S. or foreign employers. TN visas have grown from 1997 to 2022 from 168 to 33,330 for Mexican nationals.

Graph 1. Evolution of visas provided by the U.S. government to Mexican students and professional workers (F, J, TN)

However, despite this increase in the number of visas, it seems insufficient to solve the multiple challenges faced by the U.S. labor market. As Erick Miller and Laura Collins (2022) from the George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative, have recently pointed out, the American job market is in the middle of a significant realignment. This is due to workers who died from COVID or suffered long COVID, changes in the working population age, and technological shifts. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are more than 10.1 million job openings (May 2023), up from 7 million in pre-pandemic times. For example, in the case of cyber security, a strategic sector in demand of highly skilled workers, there are over 1 million professionals employed and a 40% job vacancy rate. As the U.S. Chamber of Commerce reported: "If every unemployed worker took an open job in their industry, there would still be millions of open jobs." (Ferguson & Lucy, 2023). These vacancies are even more challenging in rural and small communities.

Regarding student visas to the U.S., there are two types from which Mexican and Canadian students could benefit: F1 and J1 visas. However, the number of F1 visa holders among Mexican students has diminished from 17,636 in 2015 to 7,766 in 2022, only representing 1.8% of those given to all foreign nationals (6). This phenomenon does not seem to be a result of the pandemic. The number of F1 Mexican beneficiaries was 5,838 in 2019, one year before COVID. Students receiving F1 visas are eligible for Optional Practical Training permits (OPT). These permits have a restricted period of employment authorization of up to 12 months either before completing their academic studies and/or after completing them. F1 visas could allow the U.S. to benefit from the talent it has helped to develop, but due to the time restrictions for employment, they do not seem to be convenient for students, as only 30% of them request their OPTs (see table 1).

In contrast, the number of J1 beneficiaries has grown during the last ten years (6,735 in 2011 and 10,643 in 2021) (7). Different from F1 visas, J1 visas are not eligible for OPT permits. Even if they have increased in time for Mexican students, they will soon start to descend as there has been a significant reduction in scholarships for Mexican students studying abroad provided by the National Council for Science, Technology, Innovation, and Humanities (CONAHCYT). Scholarships allocated to study in the U.S. had a substantial 73.8% reduction in 2022 compared to 2017, and for those to study in Canada, the decline during the same period was 40.4%. This policy reduces the possibility of young people benefiting from studying abroad and using their skills for innovation and strengthening global commodity chains. It seems that neither of the three options that the U.S. has for talent development and attraction is a valuable pathway to solving the challenges of labor shortages. It is also unclear whether a regional strategy could be considered.

When examining the stagnation in the number of Canadian and Mexican students studying or training in the U.S. under programs such as F-1, J-1, or OPT extensions, it is important to note that Canadian students follow an entry process that does not always involve the visas required of their Mexican counterparts. The procedural difference contributes to the disparities seen in the statistics presented in Table 1. Nonetheless, the information highlights a decline in the rate of student exchanges within the region as of 2021.

Table 1: Optional Practical Training by Country, 2006-2021

Graph 2. Top 5 destination countries of scholarships for graduate students by Mexico's National Council of Science and Technology

Different from the U.S., Canada has understood this global fight for talent and recently, in addition to its international education strategy, has announced a plan to expand its highly skilled workforce by issuing 300,000 new visas for highly skilled migrants through the Express Entry Program 2023-202 (Government of Canada, 2020). These visas are targeted for labor needs in healthcare, manufacturing, engineering, and trade. Furthermore, Canada and Australia (8) have realized the potential benefits of bringing skilled refugees and have made their labor markets accessible for vulnerable skilled individuals (Australia’s Skilled Refugee Labour Agreement Pilot and Canada’s Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot). As a result of efforts to attract talent, the number of student permits for Mexican students in Canada increased from 4,225 in 2015 to 10,360 in 2022. Similarly, for American students in Canada, the number of student permits ascended from 5,660 to 7,020 during the same period. (9)

In the case of Mexico, the country has not been able to equitably expand the benefits of North America’s economic integration for everyone. The challenges for widespread collaboration in education cooperation toward competitiveness are also stark. For Mexico, the collaboration between the three nations in higher education has been seen as inspiring cultural competence and political-historical literacy to tackle shared challenges. However, an increased perception of insecurity in Mexico, as well as a lack of accessible financial mechanisms and normative aspects such as easily transferable credits, hinder student exchanges and shared educational opportunities (10). Another relevant challenge for Mexico is training in English among Mexican professors and students, which still presents a significant barrier that needs to be addressed in high school. This kind of work can benefit from advances in virtual education models, an area that offers universities numerous rich experiences and lessons.

In the upcoming year, Mexico and the United States will hold presidential elections. There is a significant probability that migration will be heavily politicized, particularly in the American political arena. This will make it politically costly to promote policies that facilitate the mobility of unskilled and skilled workers and to strengthen effective policies supporting educational exchange within the region.

Governors from Texas, Florida, and Arizona have been highly critical of President Biden’s administration's approach toward migrants. Paradoxically, the labor demand data shows these are states with increasing labor shortages. For example, projections for the state of Texas, show that by 2023 the state will require 26,000 additional fast-food and counter workers, 27,000 home health and personal care aides, 15,000 customer service representatives, and 9000 nurses, among others (PMP, 2021). Arizona and Florida will need additional waiters, cooks, janitors, and cleaners, as well as software developers, accountants, and general operations managers (Bahar, 2022). As Brown University’s professor Dany Bahar has recently pointed out, “The reason we see growing demand for these very different groups of occupations –some of them fundamental and some of them more advanced– is because, simply put, for each doctor in Arizona, doing her job, she must count on several fundamental workers that complement her work, from drivers and cooks to assistants and nurses. And without these occupations, the doctor simply cannot do her job.”

However, not everything seems grim. International students’ flow in the world is recovering after COVID. Now, it represents over 6 million international students with a $200 Billion economic impact. The growth of this flow has been substantial during the last years, from 2 million enrollments in 2000 to 6 million in 2020. Ten countries benefit from 60% of this international student flow (U.S., U.K., Australia, Germany, Canada, Russia, France, China, Japan, and UAE). While Canada has attracted a more considerable number of foreign students–9 times more students in 2020 than in 2000–the United States has reduced its share of the total market of international students by 17%, despite being the largest country recipient of international students. (Holon I.Q., 2023)

As a recent Holon I.Q. report underscores, technology can enhance dual-country programs and facilitate international education exchange. Students can start their degree in their home country and finish it abroad. Technology can make it more affordable to have an international study experience by paying lower fees. Despite online learning multiplying because of the pandemic, the demand for in-person classes and the possibility of having an international experience continues to be strong. Therefore, rather than viewing technology as an obstacle to strengthening educational exchange programs, it can be an effective tool that facilitates them.

Pathways for Better Interconnectedness in North America

Even if today's prospects for regional agreements in North America towards educational mobility seem bleak, there are international experiences to shed light on better forms of integration. The Bologna Process is a longstanding agreement, dating from 1999, that has sought to bring greater coherence across higher education systems in Europe. This was achieved through agreements amongst institutions, higher educational mobility (Erasmus+), and the mutual recognition of quality and credit systems.

The results and achievements of the Bologna Process in Europe are key to understanding the benefits of international educational mobility agreements. The mobility program Erasmus+ has impacted more than 9 million students (11). Additionally, students benefiting from this agreement in Europe have a lower unemployment rate than those who have not (12). The Erasmus+ program continues to be a key policy for Europe, with the European Parliament allocating 28 billion euros for the period 2021-2027, double what the program had during the previous period (13).

In the talent competition, the European Union has been implementing a series of efforts to attract and retain highly qualified workers by harmonizing the requirements of its Member States for entry and residence for third-country nationals. For example, the European Union (EU) Blue Card Directive aims to ease immigration procedures and facilitate intra-EU mobility and grand broad access to the EU labor market. Likewise, it has established a Single Permit Directive for these foreign nationals to get residence and work permits (Weigle & Zünkler, 2023).

If the region were to implement more robust policies conducive to the exchange of education and mobility of a skilled labor force, its societies could generate improved conditions for competitiveness, innovation, prosperity, and an improvement of their citizens' living standards. However, even in the future, achieving this goal appears to be a great challenge because of the politicization of migration within the presidential elections of Mexico and the U.S.

Another thing to remember is that there are elevated expectations for the potential benefits of nearshoring; the shortage of skilled labor force is one of the Achilles heels for the region to maximize its long-term opportunities. So far, the efforts of Canada, the U.S., and Mexico lack adequate coordination to overcome this challenge. The private sector can benefit from robust and proactive interaction with universities, technical higher education institutions, and community colleges. These interactions can impact expanding micro-credential training programs, leveraging technology, facilitating education, and effectively training the labor force to reallocate global commodity chains in the region. However, even if governments are not acting under this new challenge, there could be an opportunity to enact strategies in conjunction with the private sector to facilitate better results in skills formation for the three countries.

Lastly, it is important to note that the region has 55 of the 200 top ranked universities by Q.S. in the world: Mexico has two universities–Tec de Monterrey and UNAM–in the top 200 QS rankings with a population of 127 million. Canada has eight top 200 universities with a population of 39.5 million, and the USA has 45 top 200 universities with a population of 336 million (Q.S., 2023). This pool of institutions of excellence in the region could pave the way for a coordinated set of actions and strategies for skills formation that is highly required in the labor market of these three countries. This illustrates that the U.S. is in a significantly better position for talent attraction due to the great universities that are within the country. However, the programs developed by the Canadian government are helping the country attract talent that would otherwise choose to go to the U.S. This is due to visa and study policies in Canada that are more favorable to the interests of foreign students.

Right now, there seems to be no coordination in North America driving the region to compete individually for talent, rather than addressing the unresolved problems of job and talent shortages. Near-shoring, technology, and international tensions are putting the region at a crossroads. Mexico, the U.S., and Canada have an incredible opportunity to collaborate, and although the path for cooperation is unclear, these challenges should generate positive incentives for an intra-regional skills formation system. The future may appear grim, but the opportunities are present, and the governments of the region should be intelligent enough to seize them.