Long Beach has new council districts.

After months of discussions and many hours of meetings, the Long Beach Independent Redistricting Commission voted on a new map this week, setting the city’s political landscape for the next decade.

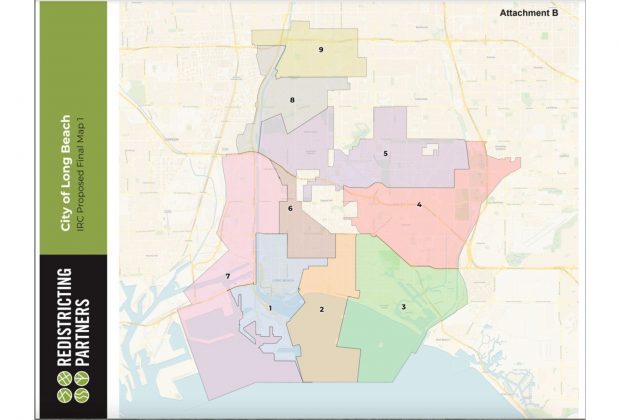

Down to two options, the commission voted on Map One, which separates Districts 8 and 5 horizontally, rather than vertically as Map Two does.

The City Council has traditionally been tasked with redistricting. But this year, that responsibility fell to the independent commission for the first time after voters implemented the new process in 2018.

The commission’s job was to reorganize the city’s nine council districts so they have close to the same number of residents following the 2020 U.S. Census. The commission also had to meet other requirements, including trying to keep communities of interest together.

The new map, which the commission OK’d on Thursday, Nov. 18, leaves both Fifth District Councilwoman Stacy Mungo and Second District Councilwoman Cindy Allen outside the lines of the districts they currently represent.

Allen will be allowed to finish her term, which runs through 2024.

But Mungo’s term ends next year. Gerrie Schipske and Michele Dobson, two candidates who previously said they would run against Mungo, were also drawn out of the Fifth District.

“I’m still in shock,” Allen said by phone Friday morning. “It was really disheartening for me to see happen.”

Mungo, meanwhile, said her supporters have encouraged her to move to the new Fifth District, but she needs time to consider that with her family.

“I am disappointed that my current residence is not eligible for candidacy for the 5th district,” Mungo said in a text message, “but plan to continue serving out my term as the Councilwoman.”

The Fifth District now stretches west past the Long Beach Airport to include California Heights and part of Bixby Knolls, under the airport’s departure flight path.

It also pushes the Sixth District east to include most of the Cambodian community. District 6 now stretches from the Port of Long Beach to the 405 Freeway, bringing the Wrigley and Willow communities together. It also moves the Coolidge Triangle neighborhood from the Ninth and to the Eighth District.

“We’ve worked really hard on this map,” Commission Chair Alejandra Gutierrez said at Thursday’s meeting.

“It is impossible,” she added, “to make all the things we’re being asked to do in one map.”

Greg Alexander, a resident, came out in support of this option.

“Map One maintains the long-standing connection between Los Cerritos, Cal Heights and Bixby Knolls,” Alexander said at the meeting. “That’s important and it can’t be ignored.”

But the map didn’t make everyone happy.

Several Latino residents spoke out against both maps. Each one reduced the number of Latinos in the First District, a historically Latino district, the Long Beach Coalition of Latino Organizations said.

These new maps, according to city data, would decrease the percentage of Latinos from 59.3% to 53% in the First District and also reduce the number of Latino voters there from 38.4% to 33.2%. That represents a change that would decrease the power of the Latino vote, the coalition and its attorney, Barrett Litt, said.

The coalition is made up of Centro CHA, Los Amigos de Long Beach, California-Mexico Studies Center, Latinos in Action, Miguel Hidalgo Deportivo and the Museum of Latin American Art.

“We’re very disappointed they decided on these two maps,” Armando Vazquez-Ramos, of the California-Mexico Studies Center, said in a recent phone interview. “It would lower the number of Latinos in the historic Latino District.”

The coalition groups threatened to sue the redistricting commission if one of those two maps were approved, arguing both would violate the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination in voting.

“When the Supreme Court interpreted the Voting Rights Act to require proof of intentional discrimination,” Litt wrote in a letter, “Congress quickly amended the statute to provide that it was violated if the effect of any procedure dilutes a minority group’s right to vote, regardless of whether the state intended it.”

Deputy City Attorney Taylor Anderson, however, disputed that notion.

In an email, she referred to a redistricting meeting from Oct. 27 during which Tom Willis, an attorney from Olson Remcho, a law firm that provided legal counsel to the commission, said the criteria to trigger a Voting Rights Act violation had not been met.

“You have to have a strong basis in evidence,” he said at that meeting, “that the Latino-preferred candidate in that area is being blocked.”

Anderson added that if the commission’s map had violated the Voting Rights Act, the city would have redrawn it.

The coalition proposed flipping a portion of the map to put the Ocean Residents Community Association fully in the Second District and placing the community surrounding the Museum of Latin American Art in District 1. That would make the percentage of Latinos in the First District 55.1% and make the percentage of Latino voters 40.3%, the coalition said.

But the commission opted not to do that.