By: Sandra Dibble, San Diego Tribune ~ Aug. 21, 2017

Mirian Juan had no recollections of her central Mexico hometown. Yet returning this month for the first time in 18 years, “the moment I landed felt like home,” said the 21-year-old math major at Cal Poly Pomona. “It filled a big hole in my heart.”

Juan, who was born in La Cantera, Michoacan, was one of 35 U.S. students who traveled to their native country for the first time since they were brought to the United States as children. On Monday, they crossed back to the United States—openly and legally through the San Ysidro Port of Entry—carrying precious memories of a native land that had grown distant and unfamiliar.

During their three-week stay in Mexico, they visited graveyards, churches, relatives’ homes, ancient monuments. They reconnected—and felt the disconnect of feeling unfamiliar with their native country. They grappled with loss—yet found a new sense of identity.

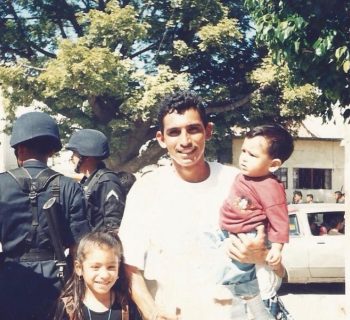

University of Wyoming student Jose Rivas, with his grandfather, also called Jose Rivas, in San Joaquin Coapango. (Courtesy)

“It’s that tug and pull of where do you belong,” said Francisca Mejía Campos, a 25-year-old senior majoring in human services at Western Washington University. She was able to reunite in Puerta Vallarta with an older brother who was forced to return to Mexico, and meet her niece and nephew for the first time.

Mejía and Juan were participants in a program run by the Long Beach-based California-Mexico Studies Center, a small nonprofit that arranges for “dreamers” from Mexico to return and learn about the country where they were born.

“Dreamers” is the term for unauthorized young immigrants brought to the United States as children who are temporarily protected from deportation and granted work permits under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program, or DACA. Created by President Barack Obama through an executive order in 2012, the program’s future is uncertain under President Donald Trump, with immigration hard-liners pushing for its termination.

The chief aim of the three-week trip to Mexico is to allow participants “to close the emotional, the psychological identity gap,” said founder Armando Vazquez Ramos, a longtime Cal State Long Beachprofessor.

This month’s group was the sixth since Vazquez Ramos founded the program three years ago. After traveling individually to different parts of Mexico, the participants gathered for their final week in Tijuana, taking a course at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte, a government think tank with sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean.

“They’re going to be main actors in the United States, so we want them to be well-informed about Mexico,” said their professor, immigration scholar Jorge Bustamante, the Colegio’s founder and former president.

The program allowed Karina Ruiz, 33, an Arizona State University biochemistry graduate, to return to the Mexico City suburb of Tlanepantla. “It was very emotional, it helped me see the privilege that I have,” in the United States, Ruiz said. But the opportunities have come with heartache.

During a visit with her grandmother, Ruiz pulled out her cellphone to show the 93-year-old woman a photo of the son she had not seen in 18 years. “She started hugging and kissing my phone,” Ruiz said.

Back with her family in La Cantera, Juan connected for the first time with her identity as a Purépecha Indian. As her grandmother helped her into a traditional Purépecha dress, the moment felt sacred, “almost as though she was dressing me for my wedding,” she said.

Josefina López, 26, born in Tijuana, did not have to travel far. A San Diego resident for the past 18 years, she is a graduate of San Diego State University with a master’s in business from Point Loma Nazarene.

Returning to her grandparents’ house in Tijuana’s Colonia Obrera, “I remembered the house,” she said. “I couldn’t remember the path to get there.”

José Rivas, 27, has spent most of his life in Wyoming, but was born in San Joaquín Coapango, a small community east of Mexico City. Back in Mexico for the first time in 21 years, he re-connected with his grandfather, and with an uncle who had been deported to Mexico.

“I have so many dreams,” Rivas said as he prepared to go back to Wyoming and resume his life in the United States.

And now he has memories, too.

Source: San Diego Tribune