By: EFE News, Los Angeles, August 28, 2020

The memory and legacy of Mexican journalist Rubén Salazar are still alive 50 years after his death at the hands of Los Angeles sheriffs, a death that still raises doubts and accentuates the controversy over police brutality against minorities in the United States.

Salazar died on August 29, 1970 by a tear gas projectile fired by an officer of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department (LASD) when he was inside a bar in the East of the city.

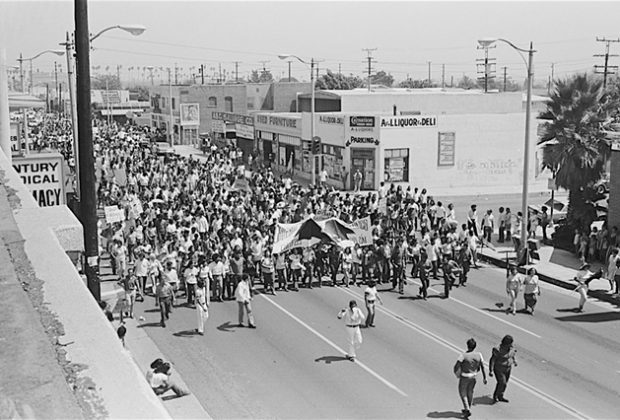

The 42-year-old journalist had taken refuge in the place with other colleagues while covering a massive demonstration, the largest of its time in Los Angeles, which brought together Mexicans and immigrants against the Vietnam War and the iniquities that this community suffered, and that it was violently dispersed by the authorities.

WAS IT AN EXECUTION?

California State University Long Beach professor Armando Vázquez-Ramos describes the journalist's death as an "execution," even if it is figuratively speaking.

"It was an execution because with the death of Rubén Salazar, the first Latino voice that was denouncing the police abuses against Mexicans, Chicanos and immigrants at that time was silenced," Vázquez-Ramos told EFE.

The professor highlights the fact that Salazar thought he was being followed that day, after exposing in his columns in the Los Angeles Times abuses of power by the LASD and the L.A. Police Department (LAPD).

One of his last columns, "A Beautiful Sight: 'The System Working The Way It Should'", published on July 24, 1970, talked about the death of two Mexicans at the hands of seven LAPD officers, a text that unleashed a remarkable controversy in the city.

“When a police officer kills a civilian, things are not so clear. When there is a question about the officer's behavior in such a death, the case is sometimes handed over to the county grand jury, where it is handled in secret”, Salazar questioned in his column.

This was not the first time that the journalist delved into police brutality against Mexicans, racism, immigration and the Mexican identity, among others. These issues had become a constant that even led to problems with the head of the LAPD of the time, Ed Davis.

THE LOS ANGELES POLICE, AN OCCUPATION FORCE

The emeritus professor of the Annenberg School of Journalism and Communications of the University of Southern California (USC), Félix Gutiérrez, explained to EFE that by 1970 the Los Angeles Police were an "occupying force in many ways."

"There was a conflictive relationship, particularly in 1970, when there were violent clashes between the police and the people of our community, and killings at the hands of the agents," he adds.

Added to this was that the force was mostly white. There were very few Latino officers and there was no one in the public bodies that supervised the police willing to see this situation, Gutiérrez clarifies.

Philip Montez, regional director of the Civil Rights Commission of the United States at that time and a confidant of Salazar, has assured in several interviews with local media that "the system did not like what the journalist was reporting."

AN ICON IN LATIN JOURNALISM IN THE U.S.

It was precisely this need to report on the social injustice that migrants and their families experienced that made him an icon and hero of Latino journalism in the country.

"Rubén Salazar was the first reporter for a notable newspaper in the United States who wrote about Mexicans in the country not as a race of brutes, but as human beings," the Los Angeles Times journalist Gustavo Arellano warned EFE.

Born in Ciudad Juárez, Salazar was eight months old when his parents moved to El Paso, where he attended public schools and the University of Texas at El Paso.

He received a bachelor's degree in journalism and began his career at the El Paso Herald-Post, where the depth of his investigations made him stand out.

In May 1955, he was arrested to spend 25 hours in the El Paso jail and write the article "I lived in a chamber of horrors" (I lived in a chamber of horrors).

File photograph from 1966 provided by the Library of the University of Southern California (USC) where the Mexican journalist Rubén Salazar appears in Mexico City, Mexico. EFE / USC Libraries / EDITORIAL USE ONLY / NO SALES

After being the first Latino reporter for the Herald-Post, he moved to California where he was hired in 1959 by the Los Angeles Times, and became the newspaper's first Latino correspondent abroad. He was covering the Vietnam War and reporting from Mexico City.

From that moment he caught the attention of the authorities. According to the documentary "Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle (2014)" the FBI had him in their sights when he was in Mexico.

Salazar was also the first Latino columnist for the LA Times, a job he alternated in 1970 with the management of the Spanish channel KMEX, now Univision 34, where he also continued his work to expose the problems that plagued the community.

In this sense, Vázquez-Ramos clarifies that "Salazar was not an agitator but a voice," which drew attention to the community.

"He was a pioneer, the voices of protest that we hear today against the brutality of the police and the abuses of the (President Donald) Trump administration have been achieved because people like Salazar led the way," he points out.

The death of the Mexican journalist was classified as an accident. For more than 40 years the LASD authorities did not give public access to the investigation.

In 2011, a report from the Independent Review Office, which evaluated thousands of pages of the file, found that the agents made a number of tactical errors, but there was no evidence that they intentionally attacked him.

After his death, the name of Rubén Salazar has been preserved for decades through journalism awards, parks, libraries and schools in California and the nation.

"His influence runs to this day, and will continue for centuries," concludes Arellano.

By: EFE News, Los Angeles, August 28, 2020