By Linda Greenhouse ~ NY Times ~ October 11, 2018

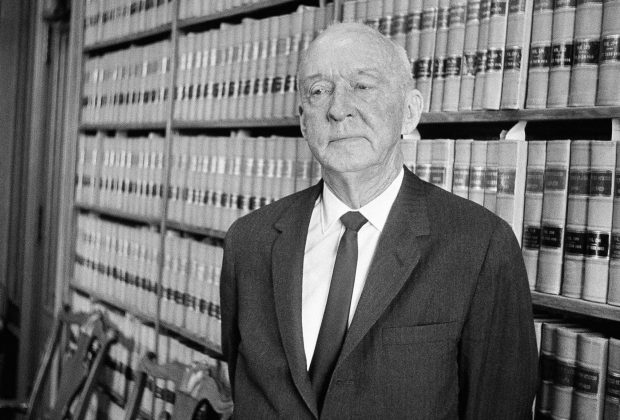

Hugo Black rose from his past in the Ku Klux Klan to become one of the great civil libertarians.

It’s obvious why the parallel between the battle over Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination and that of Clarence Thomas 27 years earlier grabbed the public’s attention. In both cases, late-breaking allegations threatened but failed to derail the confirmation process, and both nominees defended themselves with impassioned denials of wrongdoing.

But history offers another, older parallel that in its way is even more compelling. The issue was not sex but racism. The bombshell burst not just before a confirmation vote, but just afterward, forcing a newly confirmed Supreme Court justice to take to the airwaves to defend himself against mounting calls for his resignation. I’m referring to the experience of Hugo L. Black, the first Supreme Court nominee of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the wake of the Kavanaugh confirmation, this nearly forgotten episode is worth resurrecting after 81 years.

Black was a Democratic senator from Alabama, a populist and ardent supporter of the New Deal who had backed the president’s failed plan to add additional justices to the Supreme Court who could outvote the conservatives who were invalidating major New Deal programs. The retirement of one of those conservatives, Willis Van Devanter, gave Roosevelt his first chance to make a dent in the Supreme Court.

Black’s nomination in the summer of 1937 was controversial, not only because it was a sharp stick in the eyes of the president’s many political enemies, but because of Black’s limited judicial experience — he was briefly a police court magistrate — and an education viewed as marginal for a Supreme Court justice. Although a graduate of the University of Alabama Law School, Black had never gone to college.

Shortly after the president announced the nomination, rumors circulated that as a young lawyer in Alabama, Black had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. The N.A.A.C.P. asked for an investigation, but a Senate Judiciary subcommittee rammed the nomination through to the full committee after two hours of consideration. One Democratic senator, William Dieterich of Illinois, accused other senators of trying to “besmirch” Black’s reputation. As the historian William E. Leuchtenberg described the scene in a fascinating 1973 article, “Dieterich’s tirade nearly resulted in a fist fight” as another Democratic senator charged at him.

Supreme Court nominees did not ordinarily appear at their confirmation hearings in those days, but Black’s supporters said he had assured them that he had never joined the Klan. The full committee moved the nomination to the Senate floor. Black was confirmed by a vote of 63 to 16, and the new justice and his wife set sail for a European vacation.

In mid-September, while Black was in Paris and the court was getting ready to open a new term, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published the first of six articles conclusively linking him to the Klan. Soon, the country was in an uproar. The Klan stood for violence not only against African-Americans but also against Catholics, who were prominent among Roosevelt’s most loyal supporters. Catholic members of Congress demanded that Black step down. Senator David I. Walsh, a Democrat and a former governor of Massachusetts, charged that “Black obtained his nomination and confirmation by concealment and thereby deceived the president and his fellow senators, especially the latter.” A Gallup poll found that 59 percent of the public believed Black should resign if the charge was true.

On his return to the United States, Black gave a national radio address, as unusual then as Brett Kavanaugh’s appearance on Fox News was this month. Carried by 300 stations on three radio networks, the speech attracted the second-biggest audience of the decade, outdone only by the abdication speech of King Edward VIII. Black conceded that he had joined the Klan and said he had resigned before he became a senator. He neither explained his decisions nor apologized for his membership. In fact, in Professor Leuchtenberg’s account, “He spent the first third of his remarks cautioning against the possibility of a revival of racial and religious hatred, but he warned that this might be brought about not by groups like the Klan but by those who questioned his right to be on the Supreme Court.”

The national press excoriated the speech as thoroughly inadequate, but Roosevelt discerned accurately that “it did the trick,” as he told his confidant James Farley. A new Gallup Poll showed that a majority of Americans now believed that Black should not resign. He was on the bench when the new term opened three days after his speech, went on to serve for 34 years, one of the longest Supreme Court tenures, before retiring in 1971 at the age of 85.

And here’s the point: During those 34 years, Hugo Black became one of the great civil libertarians in Supreme Court history. One of his early opinions, Chambers v. Florida, overturned the murder convictions of four African-Americans on the ground that their confessions had been coerced in violation of the right to due process. He wrote the majority opinion in Engel v. Vitale, holding that official school prayer in public school violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. He wrote Gideon v. Wainwright, granting indigent criminal defendants the right to counsel. He wrote for the court in Wesberry v. Sanders, a landmark reapportionment case requiring congressional districts to be of equal population. The list goes on. That Black is celebrated today as the ultimate champion of the First Amendment may explain why the Klan episode that convulsed the country has largely been lost in the mists of time.

During Hugo Black’s first days on the bench, Arthur Krock, a columnist for The New York Times, paid a visit to the Supreme Court to observe the new justice, much as journalists flocked to the court this week to watch Justice Kavanaugh. I find Krock’s rendition of the scene, which appeared in The Times on Oct. 12, 1937, almost eerie in its current resonance:

“Mr. Justice Black’s courtroom demeanor provided material for interesting study. His face had gained color. His manner had acquired content. He looked benign instead of harried. But now and then, as the chief justice read the orders and Mr. Justice Black looked out upon the lawyers and spectators from the impregnable fortress of life tenure, an expression touched his face which is common to certain types of martyrs. It was a mixture of forgiveness and satisfaction, of pity for unreconstructed dissenters and sympathy for himself who had borne so much in comparative silence.”

The question that matters now about Justice Kavanaugh is whether his tenure, which might well be as long as Hugo Black’s, will prove his detractors right or wrong. Speaking Monday night at the nakedly political White House ceremonial oath-taking, during which President Trump apologized to his successful nominee “for the terrible pain you have had to endure” during “a campaign of personal destruction,” Justice Kavanaugh said he had “no bitterness.” He would be a “force for stability and unity” on the court, he said, adding, “My goal is to be a great justice for all Americans and for all America.”

It may be decades before we know whether he has achieved that goal. Speaking only for myself — like Justice Kavanaugh, I prefer the sunrise side of the mountain — I hope he does.

Source: Linda Greenhouse ~ NY Times ~ October 11, 2018