The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program remains controversial.

By Danielle Douglas-Gabriel and Susan Svrluga | The Washington Post | JUN. 30, 2022 | Photos by Albin Lohr-Jones/Sipa via AP

When Sadhana Singh saw President Barack Obama announce a new program for young undocumented people brought to the country as children, she felt a surge of hope.

Singh, whose parents had left Guyana when she was young, was at the time a 26-year-old in Georgia, longing for education and a meaningful career but unable to work legally.

But Obama’s announcement 10 years ago offered a new chance. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program has allowed hundreds of thousands of eligible young people whose immigrant parents brought them to the United States to get benefits such as a Social Security card, driver’s license and two-year work permit. It also opened the door for many to go to college.

“I immediately understood it meant a kind of salvation for me,” Singh recalled recently.

Still, DACA’s impact has always been tempered by uncertainty. Critics said it was created unlawfully and rewarded illegal immigration. It was threatened during the Trump administration, and new applications are suspended because of ongoing litigation. A Texas federal court last year ruled in favor of Republican officials who argued that the Obama administration had no authority to create the program. The Biden administration is appealing the decision, with a hearing scheduled for July.

At Trinity Washington University in the nation’s capital, where about 10 percent of full-time students are DACA beneficiaries, President Patricia McGuire said they are impressive, highly motivated students who have raised the school’s graduation rate. “Unless the policy changes,” she said, “all these fabulous graduates will be facing a dilemma.”

Singh, who graduated from Trinity with the support of a TheDream.Us scholarship, now works for the nonprofit and said nearly 2,500 of its scholarship recipients have graduated college. Their impact has been inspiring, she said. At the same time, she hears their anxiety, the sense that “the ax could drop any time for them.”

Like many, Singh became exhausted by all the years of uncertainty. She and her husband moved to Canada and, after two years, they were granted permanent residency there — an enormous weight lifted, she said. “All of the anxieties are gone.”

Four DACA recipients look back on the impact of DACA over the past decade and consider its challenges for the future:

Indira Islas, 24, Washington, D.C.

Indira Islas was 6 when her parents migrated from Mexico to Georgia to escape violence. Being physicians in rural Mexico made her mom and dad targets of the local gangs, Islas said. Leaving meant sacrificing their careers, but staying could have cost them their lives.

One of her fondest memories of Mexico is playing with medical instruments at her parents’ clinic. Watching them care for the community inspired Islas to want to be a doctor.

“We had a clinic in our home, so I got a front-row seat to all of the work that they did,” Islas, 24, said. “It stayed with me.”

But Islas said her road to higher education was one of the most challenging parts of being undocumented. Becoming a DACA recipient as a teenager gave her the freedom to work and get a driver’s license, but it could not provide a path to affordable education.

Islas’s home state of Georgia bars dreamers, as DACA recipients are known, from paying in-state tuition and attending some of its top universities. Her parents, who traded lab coats in Mexico for poultry plant smocks in Georgia, could not cover the cost, especially with six other children.

“As an undocumented student in high school, there were very limited resources,” Islas said. “I would go to my counselors, and none of them could help me navigate the [college] process. I was on my own.”

Through her high school chapter of the Hispanic Organization Promoting Education, Islas learned about TheDream.US, which provides scholarships to DACA students. She was awarded a full scholarship to study biology at Delaware State University, a historically Black institution. There, Islas said she felt welcomed and wanted, something she never experienced in Georgia. She was struck by the parallels in the adversity she faced pursuing an education and the discrimination that made HBCUs necessary.

Esder Chong, whose family migrated from South Korea when she was 6, is a DACA recipient. (Family photo)

Esder Chong, 24, Cambridge, Mass.

When Esder Chong’s parents heard about DACA a decade ago, they were wary of the program, she recalls. Was it a ploy to draw out undocumented immigrants? How would the government use their information? What were the long-term implications?

Chong’s family migrated to New Jersey from South Korea on a temporary visa when she was 6. They remained in the country after their visas expired in 2008, the same year her mother lost her job. DACA offered Chong and her two sisters an opportunity to continue their education without the threat of deportation. Still, so many avenues were closed to them.

“I didn’t qualify for any federal aid — loans and grants, and at the time state financial aid wasn’t open to us, either,” said Chong, 24, who is the middle child. “A lot of scholarships were limited to citizens or legal permanent residents. Colleges didn’t know what to do with us. They weren’t as informed about DACA or undocumented students back in 2016 as they are now.”Islas, who attended college in Delaware, and her parents made it a tradition to take a photo in front of the sign when her parents dropped her off for college each year. (Family photo)

“There were similarities in our stories,” Islas said. “It was pretty special … a lot of the professors were people of color and understood why we were there.”

Islas went on to pursue a master of public health at George Washington University, graduating this spring. She is set to begin a public health fellowship with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute in August, with plans to apply to medical school in the near future.

As the oldest of her siblings, Islas became her family’s college adviser, helping her two sisters apply for the same scholarship she received. They both scored the award and acceptance to Trinity Washington University. While one is a DACA recipient, the other’s application is indefinitely on hold because of the ongoing court case.

“It’s heartbreaking to see my sister miss out on milestones like getting her license and struggle with this process,” Islas said. “She is kind of the reason I became an advocate.”

Islas’s advocacy work, talking to lawmakers and sharing her story, initially gave her parents pause. Both are contending with deportation orders and worried about bringing more attention to their family. They came around.

“My parents made very big sacrifices so my siblings could have a better life,” Islas said. “It’s still uncertain for us, but we are thankful to be in this country, regardless of our current situation.”

Esder Chong, 24, Cambridge, Mass.

When Esder Chong’s parents heard about DACA a decade ago, they were wary of the program, she recalls. Was it a ploy to draw out undocumented immigrants? How would the government use their information? What were the long-term implications?

Chong’s family migrated to New Jersey from South Korea on a temporary visa when she was 6. They remained in the country after their visas expired in 2008, the same year her mother lost her job. DACA offered Chong and her two sisters an opportunity to continue their education without the threat of deportation. Still, so many avenues were closed to them.

“I didn’t qualify for any federal aid — loans and grants, and at the time state financial aid wasn’t open to us, either,” said Chong, 24, who is the middle child. “A lot of scholarships were limited to citizens or legal permanent residents. Colleges didn’t know what to do with us. They weren’t as informed about DACA or undocumented students back in 2016 as they are now.”

Chong found a scholarship that allowed her to attend Rutgers University in New Jersey, where she studied philosophy. While there, she took advantage of internships and fellowships that would never have been possible without DACA, Chong said.

Upon graduation, she was accepted as a Schwarzman Scholar to pursue a master’s in international relations at Tsinghua University in China. But Chong could not leave the country and risk her immigration status. In a twist of fate, her entire cohort was grounded in the United States once the coronavirus struck, forcing them to complete their education online. This spring, Chong graduated with a second advanced degree: a master’s in education policy from Harvard University.

Despite her successes, her immigration status, specifically the need for recipients to renew DACA every two years, has left Chong in a perpetual state of insecurity.

“When employers ask where do you see yourself in five years, I can’t answer that, because I live in two-year increments,” Chong said. “It’s hard to plan my future when the only temporary status giving me any safety and security is under threat. This is my reality, and I’m becoming numb to it.”

Chong said these days she is most concerned about her parents and other undocumented immigrants who have no meaningful protection. The focus on a select group of immigrants is a disservice to the majority of undocumented people without DACA, she said. While a pathway to citizenship is a laudable goal, Chong said that a better pathway to permanent legal residency is critical to immigration reform.

“We need a pathway to legalization and to focus on the people who are not included in the conversation” during this anniversary, Chong said. “If we do have a sense of urgency for immigration reform, the spotlight has to shift from DACA to the undocumented community at large.”

Marisela Tobar, 26, Montgomery County, Md.

What Marisela Tobar remembers of El Salvador are just fragments: Her pet chicken. The shape of the mountain outside their door. The smell of fish cooking. The feel of her grandmother, her presence. The wonder and confusion of sleeping outside for weeks, feeling the rumbling aftershocks of a massive earthquake in 2001.

And the song that was on the car radio when she sat in the back seat as they drove through a market the morning her family fled to the United States. She was 5.

Her parents wanted their children to get a good education. Growing up in Maryland, Tobar learned to love school. She also learned that her family could not travel like other families over spring break and summer vacation. She learned her father couldn’t argue if he didn’t get paid on time. She learned the words “raid,” and “deportation.” She learned the family might be separated at any time. “I was completely, always, worried,” she said.

She had a calling to become a teacher, she said, but knew she couldn’t do that without a college education. “It was difficult to dream,” she said, “because you couldn’t find a way through to your dream.”

She thought she might be able to work her way through Montgomery College, slowly, as she saved enough money for tuition one class at a time.

She was at Six Flags America with friends, an end-of-the-school-year trip when she was a junior, when her mom texted her about DACA. “It was a lot of words, and it felt so unreal,” she said.

But as she learned more, she knew, she said, “It was going to completely change my life.”

With DACA, she had the confidence to talk with counselors and admissions offices about teaching. She applied for a TheDream.US scholarship and Trinity Washington University. “I suddenly had a plan, and I was going for it,” she said.

At college, she was constantly learning, she said, “learning my craft, learning what I wanted to do, learning about the world.”

“I loved it,” she said.

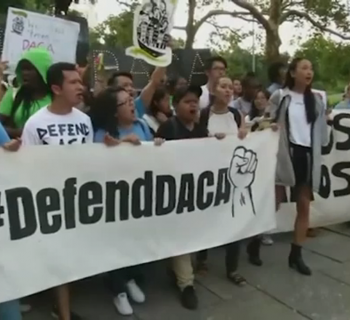

Then one day, a professor stopped class after hearing news. DACA had been paused; the future was unknown. Tobar and many classmates rushed to the White House, joining a spontaneous protest, shouting, “You’re taking away everything!”

“That was our way to grieve,” she said. “I felt like something was lost. Like you lost someone.”

As DACA ping-ponged through courts, she has felt acutely aware that the government has all her information and that she is vulnerable. It has gone back and forth so many times, she said, that she has lost track.

She’s now teaching third grade in Montgomery County, grateful for the education and the experience. “I’m able to do what I love,” she said, in a classroom with children every day. “I’m serving the community.” But she’s exhausted, too, by the uncertainty, and dreaming of a more permanent reality.

DACA was amazing, she said. “It changed my life. Ultimately, I don’t want my life to stay like this.”

Eddie Ramirez, 30, Beaverton, Ore.

Eddie Ramirez held his breath as he walked into a federal building in Oregon. He had been taught, over years of hiding, the conversations not to have, the places not to go.

Now, looking for the immigration office, knowing he would have to get fingerprinted, he wondered: “What if this is the trap? What if I’m detained? What if all of a sudden I’m going to be deported?”

His parents stayed in the car outside, frightened. They paid for three hours of parking. Ten minutes later, he walked out, with his life beginning to transform.

“I don’t even know how to put it into words,” he said. “Such a big change happened so fast.”

When his DACA application was approved, he said, “For the first time in my life, I have something with my name on it, my picture on it, my date of birth, but also it said, ‘United States of America’ on it.”

His parents had brought him to the United States from Mexico when he was about a year old. From the time he was 8, he knew he wanted to be a dentist — something about the work he saw from helping his aunt, cleaning up blood, being in the office, seeing how patients responded to the dentist.

He wasn’t much older when kids at school told him his parents, who were working as a waitress and a truck driver, were “illegals.”

So even though he worked hard and was a top student at his high school, he knew that college — let alone years of dental school — would be difficult, likely impossible.

He was accepted at Portland State University, but his mother told him there was no way they could afford it.

Just before he withdrew, he got a call from his French teacher, a favorite in high school: Her family was going to give him money for tuition.

At Portland State, he volunteered with the admissions office, helping to recruit first-generation Latino students and leading tours. With DACA, he was suddenly eligible to be paid, like all the other students, for the work he had been doing for the school. He was able to work as a waiter, too.

Suddenly he had enough hope to apply to dental schools — and he got in, to the Oregon Health & Science University School of Dentistry.

Still, he had no idea how to pay for it. And just before he withdrew — four years after he almost gave up on college — while at work, he learned he had gotten a scholarship. His mom, with some maternal sixth sense, called right at that moment.

He cried, his mom cried, his boss cried.

He told her, “Mom, your son is going to be a dentist.”

It was four years later, on a rotation in southern Oregon, when he learned DACA would be rescinded.

It was salvaged but remains vulnerable.

Now he’s four years into his dental practice. He’s grateful but still wary. He has learned, he said, to be resilient. “It’s about turning these obstacles into blessings.” He came to Washington this month to advocate with a nonprofit, Pre-Health Dreamers, for a more lasting solution.

When he got to the U.S. Capitol to meet with members of Congress, he walked right in: He had conversations to have. He had places to go.