By JEFF BIGGERS, Salon – MARCH 28, 2021

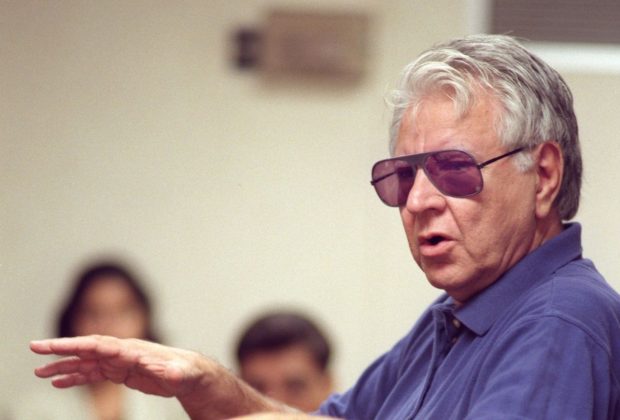

As the debate over ethnic studies brews in California and the Biden administration transitions into power, the 88-year-old founding chair of the landmark Chicana and Chicano Studies at California State University, Northridge, has little time for small talk. Notwithstanding a host of serious health setbacks over the past year, Rodolfo "Rudy" Acuña is in the process of putting together a collection of his nearly 1,000 essays, tentatively titled, "My Journey Out of Purgatory."

"Without knowing it, we leave our own footprints in life; over half my life has been in the Chicana/o Movement and related to Chicana/o studies," Acuña writes in his essay, "Footprints: The Activist Scholar." He continues: "Some of us are very fortunate because the footprints we leave can easily be traced. In my perception, footprints revive memory and memory is what prays us out of purgatory. This is important to me because I do not believe in a hereafter and I know that I will be part of this world as long as I am remembered. Purgatory is the place where the forgotten are abandoned."

Far from forgotten, Acuña remains a key figure in the corridors of cultural and ethnic studies, as a mentor to generations of scholars, and as the author of numerous seminal works in Chicana/Chicano history, including the widely read "Occupied America: A History of Chicanos." The index to his archives underscores his legacy. Yet, despite winning three Gustavus Myers Awards for the outstanding book on race relations, and receiving of the John Hope Franklin Award in 2016, Acuña has been forced to fend off or embrace the label of an "activist scholar" for a half century, including its ramifications in his successful lawsuit for discrimination against the University of California, Santa Barbara. "For the past 25 years, I have been at war with American historians," Acuña wrote in his introduction at the American Historical Association. Thirty years ago, the Los Angeles Times deemed him the "Mexican American Socrates."

"In 1989, I was awarded the NACCS (National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies) Scholar Award, which in theory was supposed to go to a Chicano or Chicana with a lifetime of activism and scholarship," Acuña writes. "I have never considered myself an activist scholar or vice versa. I consider myself a Chicana/o studies professor who uses life experiences to instruct his research and teaching."

The end result, Acuña says, matched his research topics with his own life struggles. Since he walked the picket line with Hollywood strikers with his father in 1937, Acuña has been in the trenches on all levels, as he recorded in his book "The Making of Chicana/o Studies: In the Trenches of Academe."

"In the 1960s I was involved in Head Start, voter registration, civil rights, antiwar activities and Chicana/o studies," Acuña notes. "My first three books were for public school students because I had taught junior and senior high school students as well as junior college. 'Occupied America' was motivated by my involvement during the '60s, and represents the disillusionment with the United States brought about by the Vietnam War, and its suppression of the civil rights and Chicano movements. (I had the illusion that change would come if we worked hard enough)."

While Acuña's training is as a historian, his vocation remains teaching — and his commitment is to the untold thousands of students and colleagues who cite his influence in their own lives, studies and work. "I was on academic probation, I was a troublemaker, I just wasn't really interested in school," Pierce College professor Angelita Rovero said in an interview in 2019. "Rudy, he changed my life. He really mentored me. He put a little spark in me."

"I want to be known as a teacher who cares about his students," Acuña tells me, adding, "but I need to finish this book, and I have little time before I sleep and the sharks have scattered my work."

The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

When you served as the founding chair of Chicana and Chicano Studies at CSU Northridge in 1969, where did you think the program would be in 50 years? Describe the areas in which you think it has and has not achieved such a vision.

Frankly, I knew I was one of 50 Chicano PhDs, so I just wanted to get it started and then transfer to a more leisurely environment. However, when I saw the challenge I was seduced. I had taught grades 1 to 12 and community college. Also, this was after the East L.A. blowouts and I knew it was important to give these students who had been shortchanged by the schools a place to succeed. Mexicans could learn, so I gradually was seduced. I had no vision for the future, but I knew education, and being a structuralist at heart developed curriculum. For me education is about motivation and then teaching skills. I was fortunate to build not only PhDs but good teachers such as Gerald Resendez and later Jorge Garcia. Without them we would not have survived. The reality is that we were a teaching institution and it was our job to equip them with the skills to succeed. Nothing fancy. I never thought that the program would grow as much as it has because the initial enrollment was just not there. So we concentrated on leveling the ground.

This past winter, CSUN revoked the naming of its main library after former president Delmar T. Oviatt, which students had objected to for years, dating back to his crackdown on student protests and failure to support cultural studies programs. Two years ago, the Students of Color Coalition wrote an open letter noting "the evidence of racism on campus is invisible to those who have not studied the origins and progression of history in our university," and called out "the traditional role university administrators have played" in this process. How would you describe the role of former president Diane Harrison in this regard, who recently retired after eight years of overseeing major changes at Northridge?

President Harrison was clueless. You had the feeling that she followed advice. The Fall 2020 Issue of CSUN Magazine had a cover of her commemorating her resignation. The magazine appeared to be a memorial to a white campus and featured few people of color, almost to the point that it was to attract foreign students to CSUN. Although CSUN is roughly 42 percent Latino, there were few brown faces. Harrison was not only following advice but following orders. She was a puppet. The chancellor [who runs the entire CSU system] promoted her not for her abilities, but because she was close to him. She was the president of the smallest campus, CSU Monterey Bay. To put it bluntly, she was a cheerleader who was very close to the chancellor.

As universities struggle with COVID and post-COVID scenarios, state budget issues and crises, how do you see Chicana and Chicano studies and all ethnic studies programs building on their legacies, their decades of engagement with students, staff, faculty and the local communities, and evolving over the next decade at institutions like CSUN and across the country?

It depends. Both CHS and ethnic studies are fighting over the crumbs; we will be getting the major share just because we have more students of Chicana/o or Latina/o backgrounds. However, if we are committed to ethnic studies we should be part of the solution. First, African American enrollment has fallen to 3.6% — it should be at least 10%, but this would be at odds with the business model of the neoliberal university. But we will not truly reflect L.A. until Black Americans are part of our community, so a priority should be to rebuild African Studies. So we should have a capstone course called Ethnic Studies, team taught by all departments in the family. This is the perfect time, since we can include images reflecting the multiplicity of CSUN. The pandemic is not an excuse for mediocrity.

In 2015, you wrote extensively about your concerns over neoliberalism in academia, calling it the worst threat to education. You wrote: "In order to offset the lack of public funding, administrators have raised tuition with students becoming the primary consumers and debt-holders. Institutions have entered into research partnerships with industry shifting the pursuit of truth to the pursuit of profits." To accelerate this "molting," they have "hired a larger and larger number of short-term, part-time adjuncts." This has created large armies of transient and disposable workers who "are in no position to challenge the university's practices or agitate for "democratic rather than monetary goals."

Yes, neoliberalism is hegemonic. It affects all minority communities. Unfortunately, Chicana/os and others begin to identify more with the institution than they do with their own people. That is why you have so many Hispanics for Trump. They take on the identification of the oppressor. I can say that we produced or educated more Chicana/o teachers than any institution, but cannot get even $100 for scholarships. They identify with the beauty of the buildings rather than the needs of the immigrant and in-need students. In the past, when they were here, students paid $10 a semester and an apartment was $85 a month. Now, a bed in a dorm is $900 a month. They have to buy meal tickets because the refrigerators and the stoves have been removed. There is no feeling of community or feeling of responsibility to the poor. CSUN is a teachers' college. My parents were immigrants, my grandparents were immigrants and my wife is an immigrant. I will not follow any rules or laws that discriminate against them.

By JEFF BIGGERS, Salon – MARCH 28, 2021