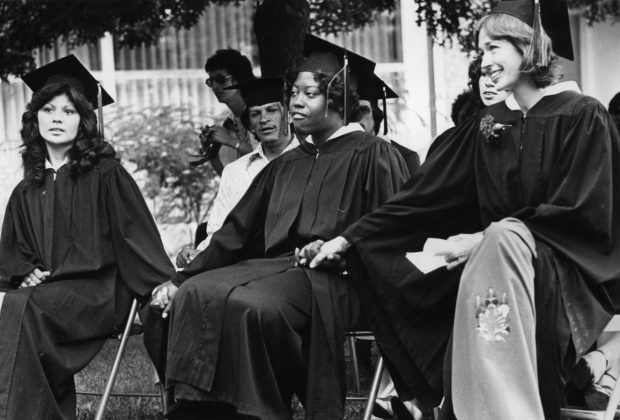

By Sami Edge | The Oregonian | SEP. 15, 2023 | Photo from The Oregonian Archives

Azael Avila grabbed a box of crayons and set to coloring a line-drawing of Mexican-American civil rights hero César Chávez. Red for the barn behind the farmworker icon. Green and blue plaid for his shirt.

Avila, a junior at West Salem High School, was familiar with Chávez from documentaries and a book his dad bought him about the activist’s life. But he’d never heard of Colegio César Chávez, an Oregon university named for the icon, until he attended a 50th anniversary commemoration for the now shuttered Mt. Angel college in August.

For a single decade starting in 1973, Mt. Angel was home to the Chicano-serving Colegio César Chávez, which historians say was the first such independent and accredited four-year college in the country. The institution focused on serving Oregon’s Latino and minority students through an education model that championed community service and gave credit for life experiences. Chávez himself wasn’t directly involved in Colegio’s founding, but he did visit several times.

“I think it was pretty cool, pretty interesting that the Latino community had something like that,” Avila said as he colored.

Colegio César Chávez closed in 1983 after drawn-out battles over inherited debt, but the school’s legacy lives on in Oregon’s classrooms and halls of power. College leaders and graduates went on to inspire and mentor Latino education advocates shaping the state today.

That influence was on full display last month when former lawmakers, superintendents, state and federal education leaders trekked to Mt. Angel to remember Colegio and discuss next steps for achieving educational equity for Oregon’s Latino students.

In the last half century, Latinos have claimed a growing share of enrollment and education leadership in Oregon’s colleges and universities. Several Oregon universities are leaning into recruiting Latino students as both a moral and financial imperative.

But higher education in Oregon is still an uneven playing field for Latino students. Latino high school graduates are less likely to enroll in college than their white peers and less likely to graduate on time if they do, according to data collected by the state.

Some think it’s time for a revival of Colegio César Chávez – or at least of the values it preached.

“They were innovative. They were community based. They wanted to celebrate the roots and culture of the student,” Beatriz Ceja, a senior director in the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Education said during a presentation at the commemoration event. “Do we still need a Colegio César Chávez? I would say we need that spirit.”

HISTORY OF THE COLLEGE

By the early 1970s, more than 32,000 Latinos lived in Oregon, yet it’s likely that only a few hundred Mexican-American students, or Chicanos, were enrolled in Oregon’s colleges and universities, according to Colegio César Chávez research compiled by Natalia Fernández, curator of the Oregon Multicultural Archives.

Leaders of a struggling Mt. Angel College saw an opportunity to meet the needs of Chicano students and revive the school. Administrators like Sonny Montes prioritized recruiting minority students and staff and in 1973 rebranded as the Colegio César Chávez.

“There was a need for bringing in and recruiting Latinos in higher education. Colleges and universities were not doing a very good job of that,” Montes said. When universities did recruit Latino students, they would “come in through the front door and go out the back,” Montes said, leaving for lack of support.

The Colegio developed a bilingual and bicultural curriculum that allowed students to direct their own studies. Though the institution had hoped to grow enrollment over time, Fernández found that most years the college had fewer than 100 students. In 1977, the college graduated its first class of 22.

Founders and former staff remember the college like a family. But times were tough. The school inherited a $1 million debt to the Department of Housing and Urban Development from Mt. Angel College, prompting eviction notices and public campaigns to save the school. Founder Jose Romero remembers cold days on campus when the school administration had no oil for the boiler. Staff made $10,000 a year, but sometimes had to donate their salaries back.

“The Colegio was my biggest challenge, my biggest thrill, the hardest thing I ever did, but I learned from it,” Romero said. “After it was all said and done, we moved on and we did some really neat things.”

Colegio César Chávez was closed by 1983, but its founders and students gained footholds elsewhere. Graduate Cipriano Ferrel started the Oregon farmworker union Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN). Montes and Romero started a leadership conference for Latino students which still gathers hundreds of students each year. A former Colegio registrar helped establish the Chicanx & Latinx studies program at Portland State.

Montes was among the mentors who helped guide future lawmaker Teresa Alonso León. As the daughter of Woodburn farmworkers, Alonso León qualified for the migrant education program in her school, and was nominated to the first class of the Oregon Leadership Institute, which brought students to experience a college campus. That’s where she met Montes, who would rally the high school students for early morning runs with a cry of “Vámonos!”, Alonso León told a crowd at the commemoration event. The institute helped instill leadership skills that would eventually propel Alonso León into the statehouse, where she became the first Latina to chair the House Committee on Education.

“Many of us who were inspired by the leaders and students of the Colegio César Chávez continued on the legacy of fighting to improve our education system for our Latino and underrepresented students,” Alonso León said.

THE MODERN FIGHT FOR EQUITY

Latino students’ enrollment in higher education is charging upward in Oregon, but students and education leaders say that colleges need to improve supports and recruit more Latino faculty and leaders.

Latino students made up about 17% of Oregon’s community college students in 2021-22 and 15% of students enrolled at public universities. The share of young Latino students in higher ed has grown nearly 40% in the past decade, according to the Oregon’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission, outpacing population growth among Latino teens. Currently about 25% of the state’s K-12 students identify as Hispanic or Latino.

Despite enrollment gains, Oregon’s Latino high school graduates are still less likely to attend college than their white counterparts and those who do are still less likely to finish their studies.

Lionila Cisneros Herrejon wants to see more efforts to help Oregon’s K-12 students make college plans before they graduate high school.

Students can struggle to afford college, Herrejon said, especially if they don’t know about scholarships or resources available to them. Latino college students are more likely to come from low-income backgrounds than white students, according to state higher ed data, and close to 40% face unaffordable college costs.

Herrejon’s three daughters attend schools in Forest Grove, where an Oregon State University extension program called Juntos works with Latino students and their families to plan for higher education. She learned through the program that if her daughters play sports, volunteer or pursue other extracurriculars they have a better shot at earning scholarships or getting into college – a future she wants for them, because she didn’t get to pursue college until adulthood. Herrejon’s family and friends in other districts don’t know about or have the same access to the program, she said. She’d like to see Juntos at every middle and high school.

“I think that’s what’s missing: more support for Hispanics so that they can achieve their dreams, their goals of having a career,” Herrejon said in Spanish.

Several Oregon universities have set their sights on becoming Hispanic Serving Institutions, a federal designation given to universities with more than 25% Latino enrollment. The recognition opens new opportunities to apply for federal grants.

Linfield University, a private school in McMinnville, and Western Oregon University in Monmouth are chasing that title. About 17% of Linfield’s students are Latino, and about 22% at Western.

Vice President of Enrollment at Linfield Gerardo Ochoa has worked to help the school build inroads with Latino families for decades. Building trust with communities historically neglected by higher education takes time, he said. Universities have to get out to community events, partner with trusted organizations and build their reputation.

“I worry about institutions that are just starting to think about it,” Ochoa said. “A billboard isn’t enough to build trust with communities.”

Administrators also acknowledge that serving Latino students takes more than getting them in the door. Universities have to support students to stay in school and succeed, Ochoa said, and building a sense of belonging is a key component.

Ruby Trujillo Lopez, a college senior originally from Klamath Falls, was drawn to Linfield in part because of the school’s emphasis on diversity. She saw online that Linfield had affinity groups such as Linfield University Latinx Adelante (LULA) and a First Scholars program that pairs first generation students with mentors and scholarships.

“I felt seen here,” Trujillo Lopez said.

Trujillo Lopez found community in Linfield’s support programs. But she thinks higher education institutions need to hire more diverse professors who can relate to students’ cultures and lived experiences. She knows the kind of discouragement that can stem from working with a professor who doesn’t recognize the challenges of first-generation students.

Trujillo Lopez was pursuing a nursing degree in her first few years at Linfield and struggling with prerequisite classes. Her advisor, a white man who came from a more privileged background than Trujillo Lopez, took a look at her grades and told her to give up, that she wasn’t going to become a nurse, Trujillo Lopez remembers.

“As a first generation student, I just said: Okay, that’s fine.’ What was I going to do? I didn’t know how to advocate for myself,” she said. His comments triggered feelings of imposter syndrome, that maybe she didn’t belong at Linfield. Trujillo Lopez went back to her dorm room and cried.

But Trujillo Lopez switched advisors and found the guidance she needed. She also feels comforted that she can turn to staff like Ochoa who understand her background and can help if she has a problem. Latino students everywhere would benefit from having more of that representative support, she said.

Ochoa said he was saddened to hear about Trujillo Lopez’ experience, which reminds him of messages he heard while in college. He personally leads some of Linfield’s professional development with faculty around mitigating bias and building an inclusive culture, and said he’s seen progress in the last five years. But sometimes, he said, “people change slower than we need them to.”

“The process of learning how to serve all our students and unlearning biases, microaggressions and more is not something that can be completed in an afternoon,” he said. “It is ongoing work we are committed to.”

CALLS TO REVIVE THE COLEGIO

As Oregon’s colleges strive to do better by Latino students, some think a new Colegio César Chávez could set an example.

“We are still not completely represented in higher education,” said Anthony Veliz, a former chair of the Oregon State Board of Education. “There is a need for an institution that really focuses on and produces top-tier bilingual, bicultural talent.”

Former Colegio founders and higher education representatives have been discussing a potential revival, Veliz said. He expects his Latino leadership network, PODER, will convene future conversations on the idea this year.

The school’s next iteration could be virtual, or through partnership with an already established university, Veliz said. Montes thinks the school could operate similar to a historically Black college or university.

“If successful, that will open the doors at the other colleges, the other universities that have been having difficulty recruiting our kids,” Montes said. “We’re going to prove to them that it’s possible to be successful in graduating from a four-year institution of higher education.”